2019 was a year of sensational cinema from all corners of the world. If there was a visible fascination for period sagas set amongst European aristocrats, Hollywood stars and vocalists, the year also saw numerous films dealing with war and PTSD. Surrealist subjects continued to serve its niche fan cluster whereas thrillers from the year were largely underwhelming. The year was more than good for campus and coming-of-age fares whereas horror and melodrama films too had their rare share of glory.

Here goes the year’s 30 finest films, ranked in reverse order:

30. Wasp Network (France, Brazil, Spain, Belgium)

An Olivier Assayas film forever fascinates. In his latest film Wasp Network, which is diametrically different from some of his celebrated fares, he tackles Cuban politics with astute understanding. One that chronicles about three stories, the central and the most interesting one remains that of Édgar Ramírez and Penélope Cruz. Ideologically, the film reminded me of 2018’s Uruguayan drama A Twelve-Year Night but only trippier and faster. The last reels, especially, are designed to please the hoi polloi, but in Assayas’ own unique style.

29. Blinded by the Light (United Kingdom)

It can be said that Chadha’s breakthrough film Bend It Like Beckham is one of the most charming and agreeable Indie films of the millennium. The film came unannounced one fine day and blew the socks off everyone – the media and the hoi polloi alike. Belonging to very same feel-good stratosphere bound by atypical Asian conservation and inadequacy, Blinded By The Light unsurprisingly carries some residue off that film. That said, this film anchored by the spectacular new find Viveik Kalra, is a lot more than a customary rehash. The story trajectory is one that alternately springs up smiles and wells up your eyes. Chadha’s film, at times, is an underdog victory tale and is otherwise a punitive coming-of-age drama. There is a major angle that makes it an intense domestic drama where the protagonist’s lower-middle-class family toils hard to make ends meet. It offers a direct portrait of racism and xenophobia in the United Kingdom and how the Asian diaspora (Pakistanis, in this film) is subjected to hate. Additionally, a film set in the late 1980s, Blinded By The Light is also a studied period piece which gets almost all the elements balanced – be it with the denim fabric used or the with aftermath of the country’s economic slowdown in the era.

28. Rocketman (United States of America)

A blingy tangerine catsuit, a headgear with feathers, horn and an outrageous, ballsy gait. As Rocketman opens, we see Elton John (Taron Egerton) waltz through a feebly lit corridor. As if he is all charged up to set another stage afire. Not surprisingly for a film of this realm, he lands up at a setup that resembles a professional rehab. With him immediately kicking off to recap his life story, director Dexter Fletcher’s adaptation of the living legend’s life takes off in great style. Now, now… this is a story that most of us are aware of – various versions of it, from the media or through plain hearsay. To lend a spin of freshness to this plot takes infinite amounts of creativity, and to Fletcher’s credit, Rocketman develops gorgeously to become a zingy and surprisingly sparkling splendour on the pop star’s life which takes fewer stops to draw a halo around him. The film, despite all the liberties, is honest and the storytelling is clearly a cut above the ordinary.

ALSO READ: 30 World Cinema Titles from 2019 That Must Not Be Missed

27. It Must Be Heaven (France, Canada, Palestine)

Elia Suleiman’s It Must Be Heaven is a fascinatingly edited film. So much so that the visuals and the symmetry draws an immediate comparison to the Wes Anderson universe of cinema. One that is extremely minimal on dialogues, the film, which also sees Suleiman as the sole protagonist, is about his quest to make a movie in Paris. What might appear to be a simplistic plot, It Must Be Heaven eventually dazzles in all its slow-motion glory with its linear and semi-absurdist screenplay forming the perfect foil to the visual kaleidoscope that it intends to be. The silver lining is how the film and the lead character’s Palestinian identity remains intact throughout even as the proceedings look incessantly glossy and Parisian.

26. The Lighthouse (United States of America)

Two men, a giant lighthouse, flocking seagulls and the ocean threatening to engulf them all. Director Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse, with its intoxicating monochrome mood in place, has the rare quality to keep the viewers immersed in its atmosphere. The temper is eerie with the minimal elements that it houses flourishing in a way that each of it become a unique contributor to making the film what is. That said, subtlety is not what the film is and it is perfectly okay. If Willem Dafoe’s delicious theatrical act is one of the year’s finest, Robert Pattinson’s fine-tuned turn which combines aggression, anxiety and a unique kind of nervous energy lends human textures to the young and flawed lighthouse guard. The cinematography and the sound design contribute powerfully to make this fierce, disturbing film what it is.

25. Fire Will Come (Spain, France, Luxembourg)

Director Oliver Laxe’s Fire Will Come opens with a disturbing visual of a slew of trees being massacred. Soon do we discover that this quaint Galician-language film is not what it seems to be. It is a one-of-a-kind film that is so confident in its skin that it astonishes us – with the way it spins drama around the most monotonous of events. Laxe’s film mere places a camera to some of the most listless lives it might be otherwise. This peculiar dramatic tone that it develops from its sheer ordinariness incessantly add to the film’s serious and topical central theme. Performances are topnotch, as is the cinematography and editing.

24. The Painted Bird (Czech Republic)

Essentially a book adaption, the only element in Václav Marhoul film is its length. Running for good runtime of three-hours, the film seems to have made an attempt to have captured the essence of the written material as it is. Having said that, the war drama is not an easy watch with its narrative filled with several gruesome plot points. Václav, very cleverly, manages to keep us on tenterhooks and eventually moving us to bits as it closes. A film that can easily be termed as an award bait one, The Painted Bird’s fable-like approach is what simplifies the experience of enduring this masterful survival drama through its runtime.

23. Honey Boy (United States of America)

Actor Shia LaBeouf’s semi-autobiographical film Honey Boy, predictably extracts a phenomenal performance from the actor. One that canvasses the life of a child star Otis (Noah Jupe) entrapped in a troublesome family unit, the film effectively addresses PTSD (not of the war-kinds), rage and complex parental equations. The characters of the father James (played by LaBeouf himself), too, is so wonderfully developed that we get an inkling of how tragic must have been the actor’s childhood. The makers do not shy away from exposing the most naked of emotions from its characters. The soundtrack has a peculiar, fresh tinge to it whereas the cinematography soaks the frames in shades of honey, literally.

22. The Report (United States of America)

One of the most shocking stories (not films) of the year is the seemingly quiet fare, The Report directed by Scott Z. Burns. Hired to investigate the questionable enhanced interrogation techniques undertaken by CIA post 9/11 is Daniel Jones (Adam Driver). Working closely with senator Dianne Feinstein (Annette Bening), the gentleman works out of a secret windowless office. It is all paper works that happen in that room but is somehow tremendously exciting. What will the ‘report’ turn out to be? How scathing will it be or how difficult will it be to safeguard the face of the agency as well as the government as far as abiding to human rights policies is concerned? The leading protagonists put together phenomenal acts and before you realize, the film touches down its rousing finale staged in the senate. The sharp dialogues coupled with its straightforward demeanour add extra sheen to The Report.

21. Weathering With You (Japan)

The anime format is one that forever delights me. The question remains about what new can be brought about in this realm of cinema. The question would be a story that milks the possibilities of anime to a T. Japanese filmmaker Makoto Shinkai’s Weathering With You utilizes that very aspect of the genre to spin a magical, fantasy romance. A worthy follow up to the maker’s own 2016 film Your Name, this wildly entertaining film is also a good discussion around a topic that is quite the need of the hour – climate change. The animation is top-notch and the plot devices are on point with its finely etched characters and coherent screenplay adding layers of realism to its plot that orbits on fantasia.

ALSO READ: 30 Incredible World Cinema Titles from 2018 That Are Unmissable

20. Jojo Rabbit (United States of America)

If we pen down the core pillars of the story, Jojo Rabbit contains mostly simple messages. It is anti-racism, anti-hate, anti-war, pro-peace, and pro-equality. In order to tick some of these the checkboxes, the film carelessly takes up certain liberties which weren’t required in the first place. The tactic to lighten a destructive episode in history was not a questionable bait but the film’s temperament is unlike, say, Life is Beautiful. Taika Waititi’s screenplay is sprinkled with oodles of humour and a lot of it is brought to us by Hitler himself (played by Waititi). The moral question arises whether it was a necessary plot to paint a vicious human being with a half-adorable tinge. Even if we exclude that layer of Hitler’s characterization, his is the least exciting track in the enterprise. The portrayal is zany and it might as well fascinate in individual scenes but, to me, his appearances functioned as pace breakers amid Jojo and Elsa’s budding friendship. Of course, the filmmaker’s intent to use Hitler as a device to mirror Jojo’s deeply indoctrinated value system might have been a clever ploy on papers but it does not quite translate.

19. Portrait de la jeune fille en feu / Portrait of A Lady on Fire (France)

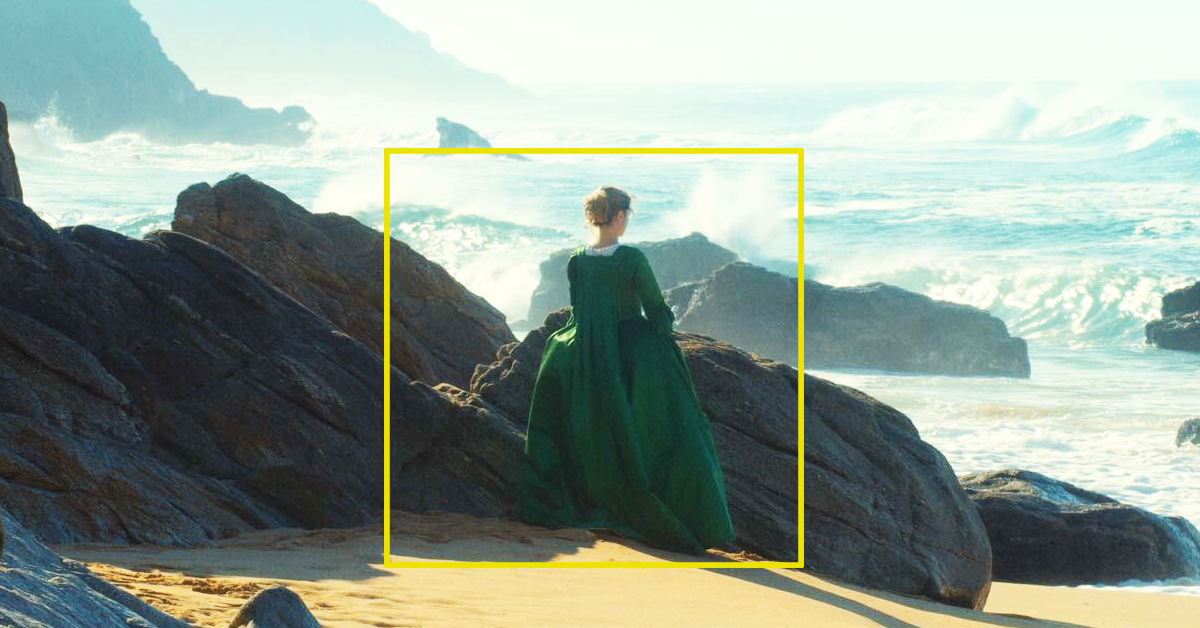

A gorgeously mounted historical drama, Portrait of A Lady on Fire is a rare film that represents gaze without violating its ‘subject’. Perhaps it is the sensitivity that a woman filmmaker brings to the table but Céline Sciamma’s film is also an intense character study which shines in its ambiguous beauty. Tackling a queer subject with remarkable empathy, the film is reminiscent of the 2017 cinematic marvel Call Me By Your Name, in spirit and soul. The visuals, as was the case in that film, are tantalizing but in a very mellow, discreet fashion. The present-day portions which see the protagonist, an artist, revealing the way her eventful love story ended feels masterful, rendering the film a sense of completion.

18. God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunija (North Macedonia)

A satire set in North Macedonia, Teona Strugar Mitevska’s film talks about pertinent issues that plague the world, and the developing nations in particular – patriarchy and religion. God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunija does a wonderful job to let its central protagonist take control for most part of her story. It is a mega win for a character thriving in a conservative society to take a bold step as Petrunija does in the film. The film talks about religious fanaticism, lynch mobs and the society’s want to show the woman her place. The writing is dexterous and the lead performance is even better. The sole hiccup is the somewhat sugar-coated ending note which looks like a convenient excuse. While it is a congenial one, I must add how it subtracts the bravado that the story organically packs along.

17. A Hidden Life (United States of America, Germany)

I have a peculiar relationship with Terrence Malik films. I either love them to bits or otherwise find them forgettable to the hilt. His latest film A Hidden Life is more aligned towards the former as it lets the story of a war-struck Austrian family bloom to perfection. More than anything, it is the DOP’s way of dramatic framing that attracted me the most to the film. Filled with brown, blue and green shades, the colour palette is a wonderful add-on to the film whose screenplay is filled with moments that exemplify valour in the hour of war. It is a great story of will power which Malik peppers with a bunch of powerful dialogues. Performances, needless to add, form the delightful icing on the cake.

16. Midsommar (United States of America, Sweden, Hungary)

Ari Aster’s film which was won major accolades already, you will realize, is an absolute firecracker as it proceeds towards the third act. One that is heavy on the story side with one twist following the other, the film acutely balances its elements of horror and absurdism. Florence Pugh as Dani is a revelation and as the film hits the final reel, you will be left with fewer gasps to make. The ambiguous and hallucinatory quality of some of the intermittent sequences are to die for, to put in the most everyman terms.

15. By the Grace of God (France, Belgium)

Now, now… here comes a film that will knock the sock off every religious establishment out there, especially the Catholic church. In contrast to its tricky title, By the Grace of God is about a group of men who are out to expose a priest who caused them severe trauma as he abused them during their childhood days. While the focus of the story is with respect to the establishment’s denial of the entire fiasco, it is in way that the film canvasses the after-effects of CSA on the victims that it earns brownie points. Sometimes severely traumatic leading to long-standing repercussions, the impact is also manifested physically by few of the victims. The only downer that I felt was in the film’s decision to take up a documentary-like route which makes the scheme of events tad repetitive until it reaches its telling finale.

14. Booksmart (United States of America)

Perhaps one of the most kickass debut features of 2019, Booksmart directed by Olivia Wilde starts off as many of the erstwhile high school romps. Two super-smart best friends, Molly and Amy, set out the night before graduation to dismantle perceptions as them being boring bookworms. The girls are headed to their batchmate Nick’s party, the venue of which, they do not know of. This incredibly witty film takes you on a mad, mad ride where the girls eventually (and predictably) emerge victorious. The writing is top-notch with some clap worthy plot-points in place that’ll make you to hoot away to glory. Ditto is the case with the finale where the girls make a thunderous entry to the graduation ground. Oh yes, the film is filled with such validating moments which truly ups the ante for this done-to-death genre.

13. J’ai perdu mon corps / I Lost My Body (France)

To make a confession, it took me a couple of watches to decipher what I Lost My Body originally intends to be. The foreign language coupled with its surrealist premise and the animation format was initially a little cumbersome for me to process as someone dabbling with multiple films at a film festival. The journey of severed hand to unravel certain mysteries, Jérémy Clapin’s film is an emotional romance in its epicenter. Sprinkled with tiny nuggets in the screenplay that add vivid shades to the film’s complex and mysterious narrative, the astonishing soundtrack also adds a superior layer of magic. While the film pointedly disentangles each of elements as it reaches the finale, one wonders if it was made complicated by choice or whether it was spontaneously so.

12. Les Misérables (France)

Debutant Ladj Ly’s Les Misérables, for most parts, has a documentery-like temperament which is not suprising given the filmmaker’s tryst with the format. The film which kicks off effectively by projecting the gritty side suburban Paris, touches upon topics such as police brutality, power dynamics in the society and the resultant chaos. The look and feel is grim and the protagonists with authority are solely male and decidedly so. As it reaches the finale, one does get a feeling of having experienced the commotion out there.

ALSO READ: 25 World Cinema Titles from 2017 That You Mustn’t Miss

11. Atlantique (Senegal, France, Belgium)

The most astonishing element in director Mati Dio’s Atlantique is the performance by the lead actress – Mama Sane – a new-find, all raw and brimming with energy. A supernatural thriller set in the Atlantic shores, the topsy-turvy writing is one that catches you unawares throughout. Coupled with Claire Mathon’s eerie cinematography (yet again after Portrait of a Lady on Fire, earlier in 2019), Atlantique is a fabulously feminist fare, inside and out. The concept, which looks a wee bit extended for the sake of generating an impact, is horrifying and utterly creative at the same time. The underlining message with mentions on class and religion that the film pack along is also noteworthy.

10. Young Ahmed (Belgium)

If handheld camera motions irritate you, Young Ahmed probably is not the film for you. That aside, this powerful Indie is a close look into a young Muslim boy’s psyche as he gets slowly drawn into radical ideas propagated by certain extremist elements in the small Belgian town that he lives in. Incessantly witty in parts, the highlight of Young Ahmed is its visceral energy. For instance, when Ahmed opens the door of moving car and escapes into the bushes, we feel the tremble and the intensity of his intent to murder his teacher. The meeting set up between the two and the way it culminates is a tense episode, the effect of which accelerates further in the last ten minutes where an exasperated Ahmed confronts her yet again. The finale does not really come up with a finite solution which makes it possibly the best way to end the film.

9. Beanpole (Russia)

Yet another film in the film that addresses PTSD, Beanpole is about two nurses during the second World War. An ex-soldier, Iya is presently employed as a nurse in postwar Leningrad. The film takes a turn when her former compatriot Masha returns. The drama that ensues from the juncture, focusing on how the war has affected the mindscapes of both the women forms the premise of this deeply empathetic film. Beanpole also creates a subtle yet stunning tapestry of a lesbian relationship between the protagonists which adds a tinge of originality to this superbly photographed and acted film.

8. Synonyms (Israel, France)

A personal favourite, Nadav Lapid’s Synonyms is the affecting story of a man’s relentless attempts to shed his Israeli roots and embrace all things French. The film begins with a young man called Yoav (Tom Mercier deliver what is the most striking performance by a newcomer in 2019) land up in Paris, making friends and dabbling with various possibilities that might make him an active, acceptable Parisian. Straight out of his military training in Israel, the penniless Yoav’s attempt to fit in an alien city is intriguing. In spirit, Synonyms felt a lot like Elia Suleiman’s It Must Be Heaven but in presence of a screenplay that believes in baring the protagonist’s emotions to the core, Lapid’s film easily more appealing to a larger spectrum of viewers. The sexual content in the film, too, is stunningly visualized and shot with extreme care.

7. Little Women (United States of America)

Greta Gerwig’s faithful, zestful and also extremely good-looking screen adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s book by the same name is one of 2019’s most loved films. Starring the talented foursome – Saoirse Ronan, Emma Watson, Eliza Scanlen and Florence Pugh – the plot is about their kindness, benevolence and selfless way of living. Spiritual in more than one ways, Gerwig’s sisterhood tale is also a fine portrait on how precisely she understands the female gender. For a literary work that has been adapted for the screen umpteen number of times, the latest version of Little Women somehow achieves greater glories purely because Gerwig’s approach to the story feels like a warm hug. The characters with their similar yet uniquely personal shades are thoroughly engaging with Ronan recreating her Lady Bird magic with Gerwig even though within a phenomenally different template. While I am not a big fan of its original score, the colour palette that the DOP picks is utterly beautiful, creating a visual language that blends with a reader’s imagination.

6. Marriage Story (United States of America)

A story that is pleasantly reminiscent of 1979 Academy Award-winner Kramer vs Kramer in spirit, the Adam Driver – Scarlett Johansson starrer Marriage Story talks about a couple with a young child facing separation. The film bluntly opens up the subject of divorce and how it is more of an emotional process rather than legal. It is a sight in itself to see Charlie (Driver) break down to bits upon confronting his to-be-ex-wife Nicole (Johannson). This is followed by an intensely vulnerable moment where Nicole herself reaches out to him, as if on impulse. The courtroom proceedings look real and unfathomable considering how you pine for the couple to solve their differences, like every sane audience member would. However, the incidents do not pan out the way you expect them to, but the ending, needless to say, is satisfying. One that comes with an eclectic music score, director Noah Baumbach’s film is a painful reminder on how divorce as a proceeding changes a family overnight, to a state of no return.

5. Le Daim / Deerskin (France)

Audacious is the word for director Quentin Dupieux’s Deerskin. Obsessed with his brown fringed coat made of the deer’s skin, the film is essentially the quest of a man named Georges (Jean Dujardin) to amass as many jackets as possible to become what must be the only person in the world to have the luxury to own a coat. The premise is ballsy and invigorating with a dulled out colour palette doing the needful in creating the critical visual ambience. The screenplay which feels like a series of events knitted together to reach the pinnacle of the protagonist’s bizarre obsession, Deerskin also contains a marvelous side act from Denise (Adele Haenel). There is an amateur filmmaking trope that the film uses as an active device which also becomes instrumental in designing a terrific culmination to the story.

ALSO READ: 25 Non-Indian Films from 2016 you must watch

4. The Irishman (United States of America)

One of 2019’s most agreeable films, The Irishman sees Martin Scorcese execute his auterial prowess to the hilt in an extremely long run-time of more than 3.5 hours. One that covers a period of sixty years, the film is decidely male in its temperament. Bearing all tropes of a brooding gangster drama, the film gleams in its surprisingly humourous skin as it pulls off the impossible of what might look like alternate perspective to Godfather 2. The cinematography is unusual for the times that we live in and so are frames selected by the editor, both of which contribute to create a gorgeous melange of emotions. Yes, I dare call it a highly emotionally involving fare for a fact that it is this very rhythm in the screenplay that makes its longish runtime worth every dime. While I am still not fully in agreement to the digital de-aging that it does on its characters, I can also not deny how Scorcese couldn’t have had better actors bringing life to them. Al Pacino, in particular, delivers what must be his most thoroughly studied and entertaining performance in decades. And if at all there were ways to justify the length of the film, Scorcese pulls a gargantuan surprise by ending the film in a fashion that is so characteristic of him yet so original and fulfilling.

3. Pain & Glory (Spain)

Pain and Glory, with its intricate layers and episodes panning through decades, is ultimately a fine character study. We delve deep into the mind space of a man who is slowly plunging into professional irrelevance. We also feel the regret in him for not having fulfilled his industrious mother’s last wish. There is a finite yet delectable taste of lost love. And last but not the least, Salvador’s passionless yet need-oriented equation with Mercedes (Nora Navas) gets its share of focus. Almodóvar makes sure that none of these chapters is overly expository. The stories – singularly and collectively – feel personal but their screen duration on papers together with the way they’re weaved by the editor is perfectly in tune.

Staged in a film set, the film’s clever finale only reminds us that Almodóvar is one amongst our cinema greats for a reason. Pain and Glory lends dignity to heartbreaks and unpleasant revelations. It makes reconciliations look organic and graceful. It is unflinchingly real to see the once-celebrated leading man dabble through physical and mental infirmities, like any other ordinary person. It is quietly affecting to see him subscribe to temporary respites, not acknowledging the actual vacuum within. Through each of these nuances, Pain and Glory proves that Almodóvar, for sure, knows his universe. He has certainly mastered the technique of making his viewers immerse in his stories and emerge with their eyes drenched, even though his characters seldom do. Not a commonplace skill that is, I must add.

2. The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão (Brazil)

I am not sure how many filmmakers from today’s date possess the merits to blend physical beauty with intense pain while manifesting them on screen. As a matter of fact, Karim Aïnouz’s Portuguese language film The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão scores a ton in the aesthetic department but is also unbelievably empathetic towards its inhabitants emotional needs. One that narrates the tale of two sisters separated by destiny (more accurately by their unreasonable father) is about how they dabble with the gritty trail that life offers them. One that boldly projects the patriarchal society in 1950s Brazil, The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão also subtly underlines the need for a feminist way of life. Highly suspenseful and equally well-acted and shot, the film is an unusual melodrama to come out in today’s time when this otherwise delightful genre is largely out of vogue.

1. Parasite (South Korea)

And this one is no surprise, I am pretty sure. I remember the day that I watched Parasite for the first time wherein I began thinking of an instance when a film had the power to leave me absolutely dumbstruck. I’ve been moved. YES. I’ve been numbed. YES. I’ve felt exhilarated, scared and have cried copious tears. YES. But, but… the multi-genre medley that director Bong Joon-ho creates with Parasite is extraordinary, clutter-breaking and resultantly a mammoth cinematic benchmark. You name the genre, Joon-ho has it in his film.

Staying true to its Indie flavour, Parasite canvasses the dingy existence of the Kim family in their rickety basement apartment. Immersive as one ought to call it, the film refuses to exist in the poverty porn stratosphere. We see how the family finds comfort in their poverty and are perennially striving to make their lives better. The eventual turn of events give the story all rights to touch unusual contours and it gradually soars to become a true masterpiece. A black comedy at its heart, Parasite exposes the poor versus rich divide in what must be the most naked way possible. The film’s stance of capitalism is offers enough food for thought while converting this essentially South Korean story to one that resonates globally. There’s no dull moment, no false note in a single performance, no indulgent frame or overwrought screenplay element. Even the tiniest of objects that make way to the screen contribute to making the film the experience that it is. What a massive win!

Special Mentions: Brittany Runs a Marathon (United States of America), Knives Out (United States of America), The Aeronauts (United Kingdom, United States)