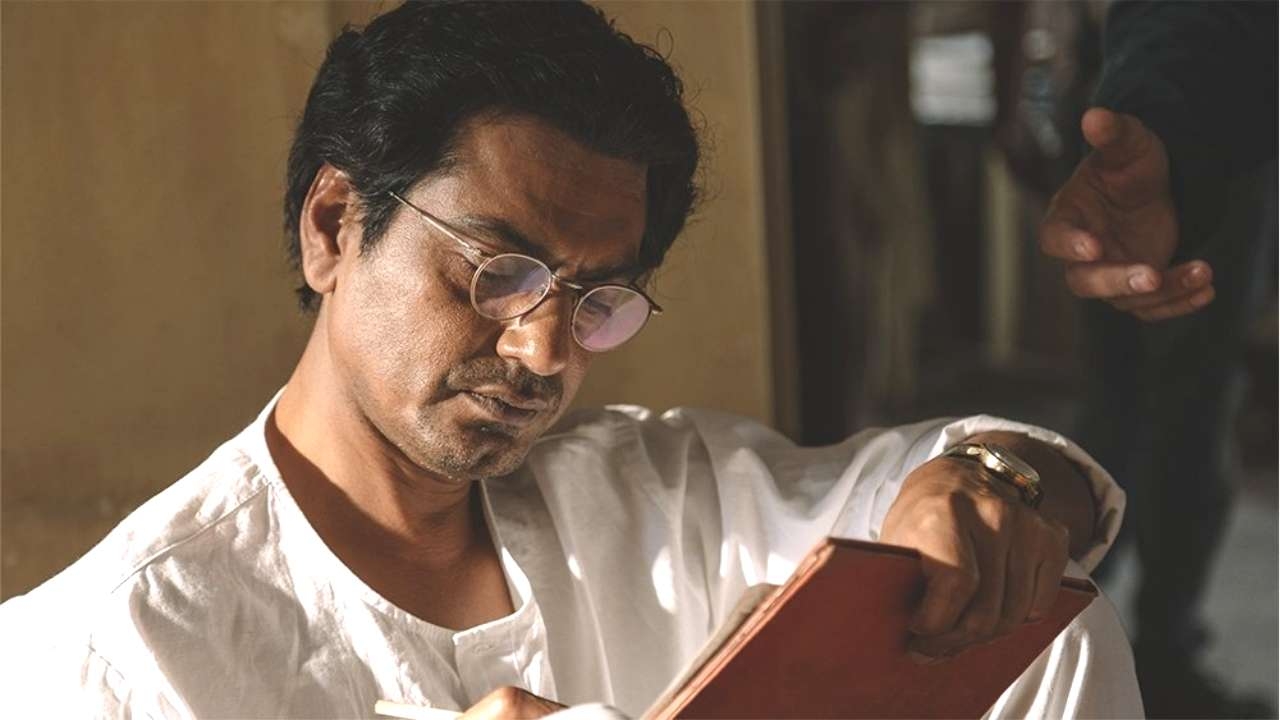

Saadat Hasan Manto. The illustrious Indo-Pakistani writer who lived in the first half of the 20th century has to be one of the most fascinating subjects for a biographical film. Given his eventful life, a curator ought to know which phase he/she needs to lay to focus on. Filmmaker Nandita Das opts for the less juicy part wherein Manto (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) struggles to obtain literary freedom and financial stability in post-partition Lahore.

“Main to chalta phirta Bambai hoon,” (translates to “I am walking, talking Bombay”) states Manto and any ardent admirer would chuckle in agreement. The writer who comfortably rubbed shoulders with the film industry bigwigs besides having a great fan following for himself, Manto’s writings were not always linguistic marvels but were often scathing and astonishingly honest. Here is the man who had the audacity to call Nargis a plain-looking girl and an artless performer. He could spell out the weaknesses that Ashok Kumar furtively bred, besides nearly calling the famed danseuse Sitara Devi, a femme fatale. The wrath that might follow his articles and stories seldom affected his spirit. Manto, who continued to be his original self, enjoyed great repute in the world of art and contributed enormously to the growth of Hindi cinema in its early stages.

With Nandita Das only momentarily touching upon Manto’s lively persona in the sparkling world of cinema (he worked for studios like Filmistan and Bombay Talkies), an unassuming viewer might wonder who the target audience is. Set in the partition era, the only friendship that the film attempts to record in detail is the one that Manto shared with actor Shyam (Tahir Raj Bhasin). A brief altercation coupled with the ongoing communal tension in Bombay forces Manto to flee the city that ran in his pen and veins.

ALSO READ: ‘Thackeray’ review – an exquisitely photographed biopic that plays safe

Slowly recovering from the repercussions of partition, the socio-political climate in Lahore gets finely etched in Manto. Shops in the neighbourhood lanes get freshly painted to suit the city’s newly acquired identity. We also observe how the city offers Manto a whole new creative canvas, which changes colours from bold, often satirical to flaunt shades of incessant tragedy. Given the melancholic mood of separation and extremism, Manto strived hard to be his own self, followed by an obscenity charge in one of his popular short stories. We see Manto slowly shed the glitz of Bombay that he was used to. A chain smoker, Manto makes way to cheaper alternatives being unable to afford those expensive cigarettes which came in fancy cases. Life had changed before he could realize it. Yet Manto continued to write.

Finding a way to introduce Manto’s spellbinding works of fiction, Das intersperses the main narrative with cinematized versions of some of his celebrated stories. This, however, works only sporadically as not many of them balance perfectly in the film’s otherwise tense plot. ‘Thanda Ghost’ adds to the flavour of the proceedings but the opening story sticks out like a separate short film. ‘Toba Tek Singh’ which appears towards the finale is integrated in too layered a manner for an average viewer to grasp.

Having said that, Manto effectively recounts the plight of those who lived through the partition era. It does not give us an answer on why Manto never returned to India (many of his counterparts did, for that matter). The narrative shift in the film comes with a tinge of exasperation – for Manto as well as for the audience because Das offers no respite in a story that gets exceedingly unexciting as it progresses. One can say that there is an element of wonder that the film will generate in someone who is acquainted with Manto’s works. He/she, in any case, belongs to a minority clan. For the rest, Manto follows a documentary-like pattern that is elevated to superlative levels by Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s pitch-perfect turn in the title role.

Additionally, in smaller parts, Rajshree Deshpande and Rasika Duggal put in excellent efforts. The same can’t be said for Bhasin whose gait and mannerisms appear way too rehearsed and rulebook-driven. A case in point is the train sequence where he explodes at Manto for giving a literary spin to everything. We also wish that the film came with a little more background to Manto’s friendships (with Ishmat and the Progressive Writers’ Association members, in particular) as opposed to his occasional run-ins with lecherous producers and callous publishers – all of which deserve a different film in every way.

Manto isn’t excessively verbal considering how its protagonist was certainly one. At the same time, the film vacillates by not offering him enough outlets for expression. Instead, we get a handful of generic characters (a laughable Shashank Arora playing someone called Shaad Amritsari) and a series of generic outbursts that could have belonged to any routine film. Das attempts to paint a nuanced picture of her subject but averts from examining several political and social constructs that had surrounded him in pre and post-partition periods. Even as a personal portrait, Manto’s story could have been a lot more captivating had it studied the days of his exciting years in Bombay. Partly a case of an opportunity missed, the film derives a great amount of its appeal from Nawazuddin Siddiqui who dazzles you completely in what appears to be his most challenging role to date.

Rating: ★★★

Manto is now streaming on Netflix.