“You are so pretty. You could be a girl.”

“You left the child with that imbecile and forgot your responsibilities.”

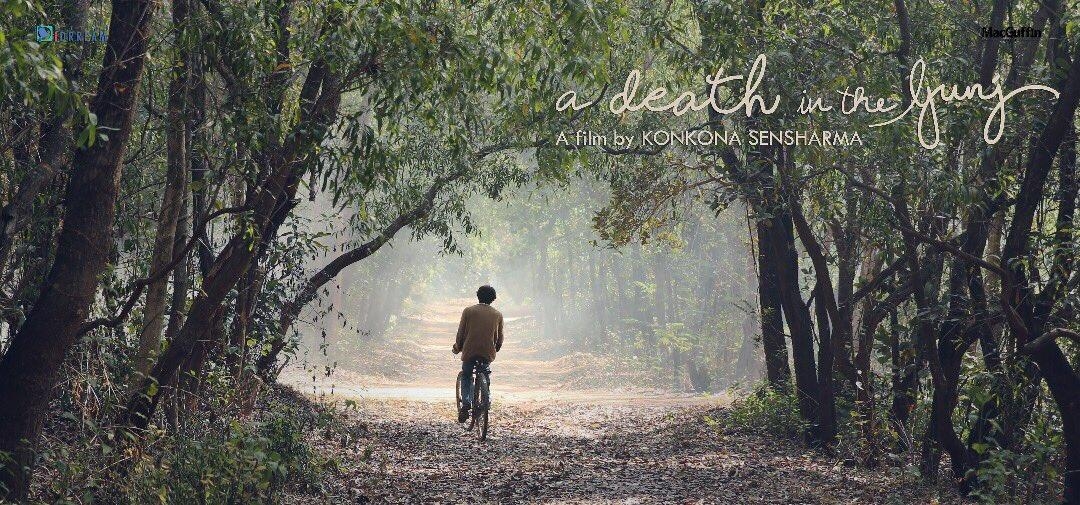

These epithets are not unfamiliar in Shutu’s (Vikrant Massey) everyday life. Shutu is meek, brooding. The latter in an unsexy way. Shutu’s cousin thinks he should toughen up and start taking care of his mother. His wife feels he’s just sensitive and needs a little hand-holding. Shutu’s grandmother has ideas too. Pretty much everyone has an opinion on Shutu’s unconventional ways and isn’t reluctant to acknowledge it. Konkona Sensharma‘s directorial debut A Death in the Gunj is set in Bihar’s (now Jharkhand) sleepy McCluskieganj and the year is 1978 going ’79.

Not just the era, A Death in the Gunj‘s resemblance to Aparna Sen’s 36 Chowringhee Lane isn’t uncanny. Dejection is a recurring motif in both. Aparna’s Ms. Violet Stoneham had seen her life pass by, the orbit of which was anything but pleasant. Ms. Stoneham’s dreary existence was not a choice and all she desired was a tint of happiness, a little laughter. She, however, didn’t seek any of it. They came to her. Konkona’s lead player Shutu is surrounded by elements that assert his glaring inadequacies. His skill set, demeanour and looks – none of it match specimens of ideal standards. Then again, he is neither inert to emotions nor particularly eccentric. He is just different – wading his way through this complex world.

ALSO READ: ‘Dolly Kitty Aur Woh Chamakte Sitare’ review – a compassionate ode to India’s working class heroines

Not just in its title, death finds numerous mentions as the film proceeds. Shutu is shown to be vulnerable to every single instant – be it the one around a planchette prank, a dead insect or a fleeting visit to the graveyard. Probably somewhere he believes that death denotes peace, and a better abode, far away from tiring, mundane life. We also hear mentions of local hunting scenes as well as grandfather’s (Om Puri being classic Om Puri) prized rifle. Every object in Sensharma’s frames serves a definite purpose. So do animals. Yes, there are plenty of them – from a puppy to a frog and even a fox. Sensharma’s writing is vivid, with sharp attention to detail. Be it the lonely passages, the state of pets at the Bakshi’s home in Calcutta, the Anglo-Indian lady’s deceased child or the way Shutu finds safety in his father’s sweater, A Death in the Gunj is all about tiny details that are often anecdotal. Even Bonnie’s (Tillotama Shome) delicious-sounding Bengali Mutton curry that absorbs all flavours from not-so-finely chopped potatoes could be a clever metaphor, if one may consider it.

Regardless of how Shutu remains the pivot of Sensharma’s story, we do notice the ensemble cast and their mild idiosyncrasies. Ranvir Shorey‘s Vikram Chaudhary is the quintessential loud, insecure, in-your-face macho man who wouldn’t leave a chance to terrorize the weakling. The traditional family-bound Nandu (Gulshan Deviah, at his dependable best) is facing the boy-man crisis and often feels the need to prove the ‘lad’ in him. Brian (Jim Sarbh) who drops by often is no less a rogue. They endure jokes on ‘family jewels’ and chastity belts with equal spirit as they include their tribal domestic helps in an aggressive game of kabaddi. It is not as if any of these men are distressingly evil. They all have their points to prove with their misled entitlement and resultant lack of empathy. The languid and the frail, by default, were meant to cultivate great fortitude to survive their energies. Deviah is terrific in the scene where he forcefully instructs Shutu on how to reverse the family car.

Sensharma’s women characters are more sensitive to Shutu’s needs barring the selfish Mimi (Kalki Koechlin). Post a brief romantic encounter, Shutu feels she could be his emotional anchor, only to discover that she had different plans. The young Tani (Arya Sharma, not overdoing the child actor act) is inquisitive to good measures in Shutu’s world of severe self-doubts. He finds solace in her company, even as they rest lazily in an abandoned bathtub in the backyard. She critiques his drawings to which he reciprocates by appreciating her eight-liner poem. Shutu’s worried grandmother (a fabulous Tanuja) veils his failures from the rest of the family until a moment of discord erupts. There’s embarrassment, seclusion and inevitable disillusionment – most of which resulted from actions that were far from intentional. All they could see was a young man in his prime, not manning up the way they want him to. Most of Shutu’s relations with the women in A Death in the Gunj meet rather unpleasant closures and his bond (or the absence of it) with men do not. Because women did care and Shutu knew it.

McCluskieganj is not a surreal picture postcard beauty. Among other things, Konkona Sensharma and hill stations take us back to memories of Titli. Just that we do not see any mist in A Death in the Gunj. While DOP Sirsha Ray‘s outdoor frames are atmospheric as expected, it is the measured pandemonium of the stuffy interiors that appealed more to me. The night when the power goes off or that of a crowded new year party where a new bride is a star, Ray’s compositions are cinematic yet so fluid. A lot of it could be attributed to the appropriate production design by Siddharth Sirohi. Sagar Desai‘s score is zingy and accentuates characters and their uneven temperaments. How I wish Sensharma’s dialogues had less of a complementary twang to them. Likewise, the climax doesn’t propel the way it should ideally have. Nevertheless, it is Sensharma’s grip over her material, some terrific storyboarding and focused execution that makes sure to cover up these oddities and induces a massive sigh as you leave the hall.

ALSO READ: The 10 Best Bollywood Films of 2017

As much as A Death in the Gunj projects Konkona Sensharma’s directorial abilities, it is also a showreel to Vikrant Massey’s histrionics. Even as he clumsily sits with his legs stuck together or when he rolls the motorbike through the courtyard – Massey is a tremendous talent and it is fortunate that filmmakers are offering him lead roles. Sensharma, on her part, makes full use of the slowly blurring lines between commercial and experimental cinema.

A Death in the Gunj has all intrigue of a chilling thriller (minus loud music). Some of her frames, interestingly, stay still for maybe an extra second or two – reminding us of fine European cinema. From what (somewhat) seemed like an outburst-driven dysfunctional family drama where every player makes a revelation each, A Death in the Gunj turns out delectably sober reminding us of similarly moody cinema by Xavier Dolan and Hirokazu Koreeda. A perceptive, fly-on-the-wall account of an ordinary family vacation gone kaput, the film is confidently mellow. Not that we expected anything less from you, Konkona. Legacy, as they say.