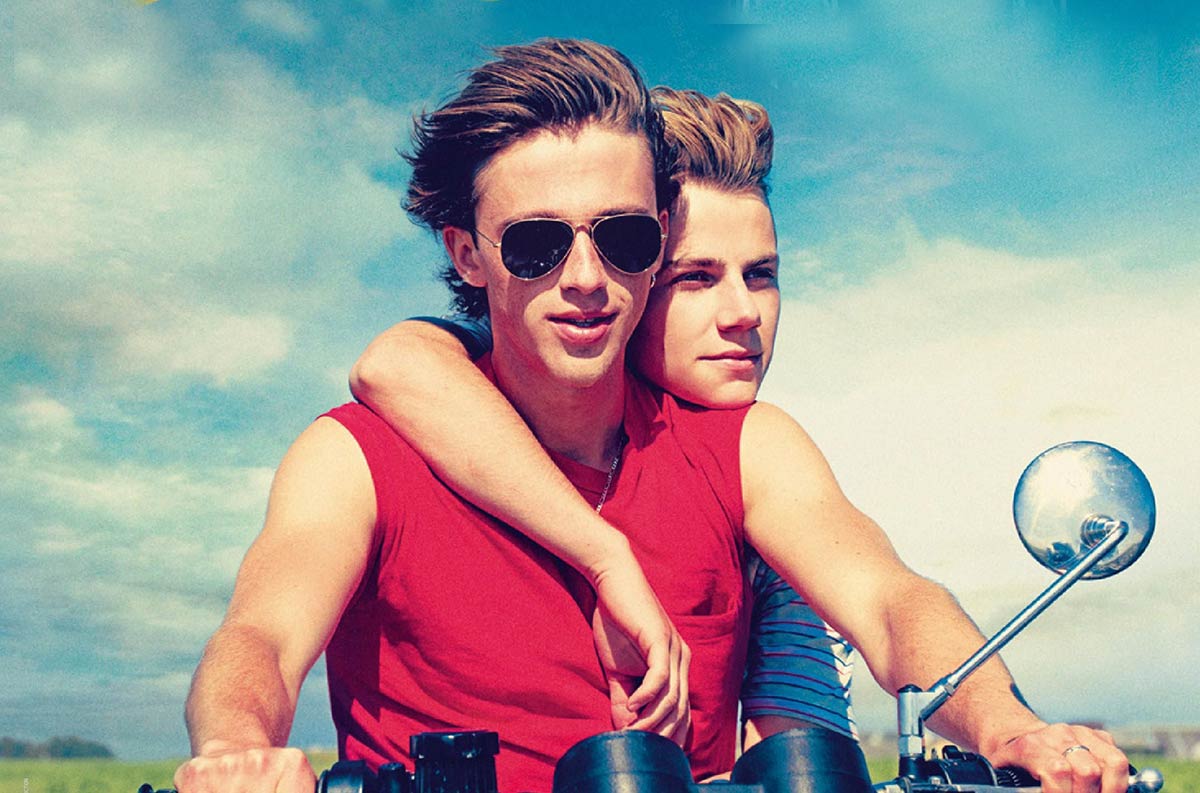

Seconds into François Ozon’s Summer of 85, the cat is let out of the bag. Teenager Alexis alias Alex (Félix Lefebvre) – the protagonist and the narrator – is in trouble linking to the death of someone close, presumably his lover. New to Normandy, Alex is capsized while sailing in a borrowed boat. Coming to his rescue is David (Benjamin Voisin) – a lean, dapper, and way smarter dude who is roughly the same age as Alex. This is where a bizarrely quick friendship ensues between the two.

David takes Alex home. There he meets his mom – who is a weirder person than the whole episode in itself. Demanding Alex that he takes a bubble bath, the lady insists on undressing the boy herself. Alex is visibly unnerved and the woman looks at his willy to comment, “your mom will be proud,” Almost suddenly we imagine how the film would eventually go on to flaunt finer shades of this eccentricity. Upon being offered fresh clothes and food, Alex is quick to ask, “You do this to every boy who capsizes?” Precisely my question.

Much to my dismay, Summer of 85 does not evolve into an amusing comedy of manners. In fact, it emerges into a mild melodrama in the subsequent acts. Ozon’s film enters almost every terrain that a gay romance is stereotypically known to.

Everyone seems to be in a hurry to make things happen in Summer of 85. Alex himself doesn’t realize how he gets dragged into a legal mess. He remains foolishly silent as his life takes a mega turn – none of which he actively sought. Of course, David is undeniably attractive and is a kind fellow. Nevertheless, nowhere during this relationship is Alex seen as an entity with any kind of agency. He is an entirely different person at home – a unit whose dynamic is difficult to make sense of.

The love story in Summer of 85 drives in a distinct sense of déjà vu. The writer injects rather mindless plot points such as David asking Alex to make a bizarre promise – whoever dies first would dance on the other’s grave. My issue is not with the twists but Ozon’s film was in an entirely different mood when it kicked off.

Summer of 85 turns better once David dies. The focus shifts to Alex, who in all honesty, is the more interesting character even though the film sides with David’s showy antics. I particularly loved the process with which Alex comes to terms with the fact that David is no more. Besides being an emotionally harrowing journey, it also hardens him and he expresses himself through his writing. His mentor – the schoolteacher – is another person who belongs to a dystopian universe but by this hour, I had pretty much given up hopes on the film and its odd character designs.

When David forges a closer bond with Kate, who in some way is responsible for the rift between the boys, the film further strengthens its core. It is thrilling to see Alex dress up a girl to catch a glimpse of David’s body in the morgue. In a brief scene staged at Alex’s home, Kate makes a series of profound points that somehow stick out in a film that lacks depth. However, the most impactful bit that the writers employ to help Alex accept himself is a reference about a certain Uncle Jack whom everybody hated but not his mom.

ALSO READ: ‘Undertow’ review – a haunting love story with an achingly beautiful finale

Performances are uneven. If Lefebvre’s approach to Alex is heart-wrenching from the word go, Voisin seldom comes out of David’s glamourous exterior. Philippine Velge as Kate springs a pleasant surprise and so do the actors who appear as Alex’s parents. Among its more pleasant sides, Summer of 85 emerges as a magnificent period piece. The ‘80s does not exist as a customary backdrop but it comes magically alive – be it with the DOP’s (Hichame Alaouie) frames or the locations (Benoît Barouh, Frédéric Delrue) and costume design (Pascaline Chavanne). The relationships and friendships, too, emerge from a framework that is organically retro.

François Ozon’s film gets its best moments in the last act. The culmination is near-flawless to a story that could never find a footing until then. It is just that I could imbibe a definite sense of familiarity with a slew of superior films in the genre. While the Call Me By Your Name resemblance would be an obvious one, I could also draw parallels with Fatih Akin’s smashing travel film in Tschick in various ways. And, honestly, I need a break from gay romances that trick us with deaths and teary, inevitable separations.

Rating: ★★★

The film was screened at the 32nd Annual New York LGBTQ Film Festival.