Amol Palekar directed Paheli. The actor who came to the limelight in the ’70s and ’80s as the young middle-class man in bustling Indian metropolises, one would identify him as the poster boy of everydayness. He was seen in stories devoid of extra colours, those with messy relationships, and in lyrical romances that emerged out of mundane spaces. Having watched a few of his directorial ventures, namely, Daayra, Thoda Sa Roomani Ho Jaaye and Anaahat, I could sense how the filmmaker is a fierce advocate of gender equality. Yet, his biggest project till date Paheli was mounted on an extraordinary canvas. Perhaps it was the Shah Rukh Khan effect but the film – from the exterior – was strikingly dissimilar from Palekar’s simple demeanour. Paheli is shot in large sets complete with elaborate costumes and jewellery. There are superstars hogging the film’s kaleidoscopic frames. Easily, the film is decidedly larger-than-life. But… but it is still a poignant story centered on a woman’s beating heart. Amol Palekar’s Paheli is as much a gender empowerment tale as Anaahat is.

An Unusual Shah Rukh Khan Film

Released on 24 June 2005, Palekar’s film was an unconventional project for Shah Rukh Khan to bankroll under his production house Red Chillies Entertainment. Why? The reasons are many. At a time when the superstar was having a helluva time – critically and commercially – a folk tale set in medieval Rajasthan was the last we expected from him. Possibly, the actor wanted to try out the audiences’ evolving taste. Secondly, despite appearing in twin roles, Khan is not the pivot of Paheli. Amol Palekar’s story is all about a newly-wed bride Lachchi (Rani Mukerji) – her desires, torments and, most importantly, choices.

The Celebration of Consent

Paheli kicks off with a marriage song. The young Lachchi is being married off to Kishanlal (Khan). While it is not told to us whether the wedding was arranged after taking her approval, it is hinted that the girl awaited to be at her husband’s home. True to the era it is set in, Lachchi must have been brought up for this big event in her life – the marriage – which would turn her into a responsible homemaker. Yet, the women around her teasingly celebrate an aspect that is duly ignored in married relationships – consent.

Minnat Kare?

Naa Maaniyo

Paiyan Pade?

Naa Maaniyo

Agar Wo Haan Keh De…

Naa Kahna

Wo Naa Kah De…

Haan Kahna

Jaan Ki Kasam De To?

Albeit playfully, the women make it clear how she ought to counter her bridegroom’s advances. When the usual ‘main saajan ke ghar jaungi’ vibe surrounds run-of-the-mill Bollywood wedding songs, ‘Minnat Kare’ is a cracker of a song in the genre.

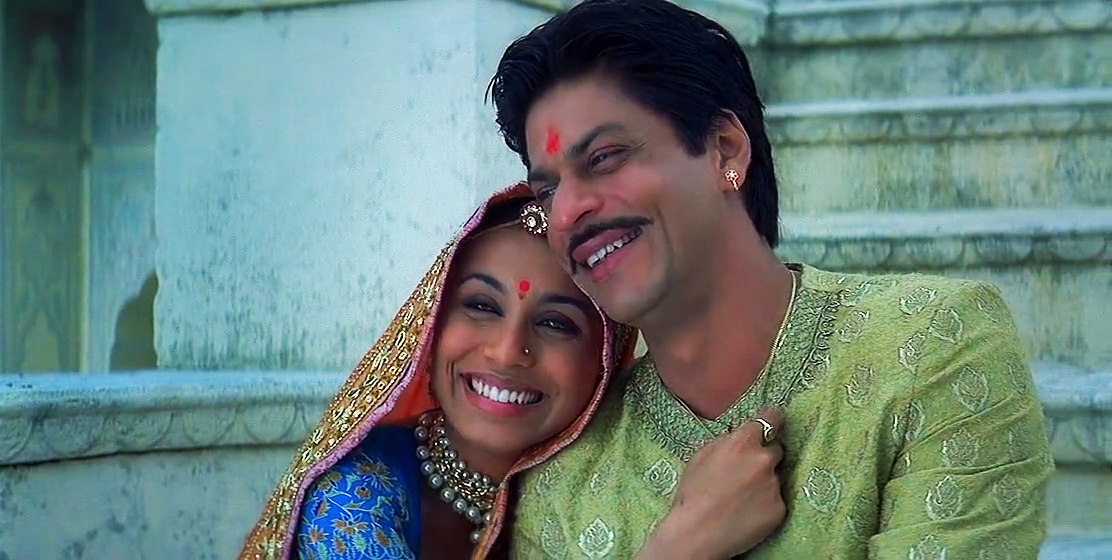

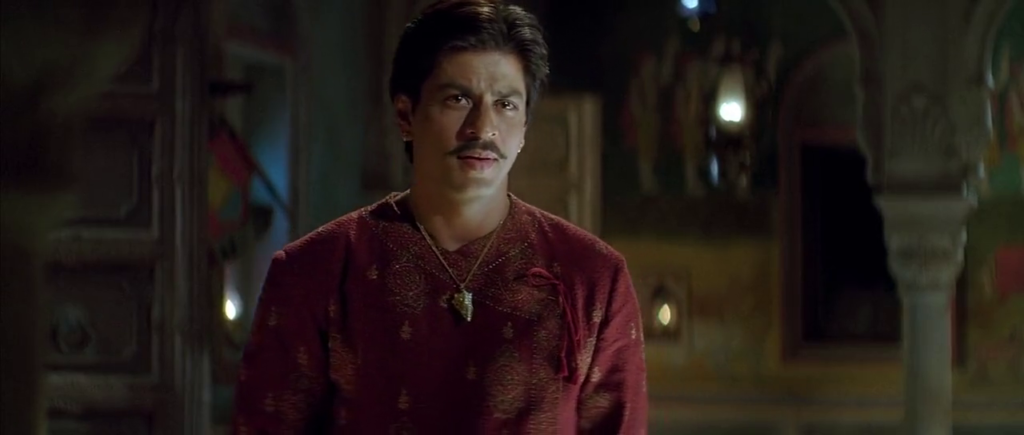

Supernatural Khan in a Woman’s World

To be honest, it is a little difficult to sit through Kishan Lal. Not necessarily because it is a bad act from Khan’s end. The actor knows what he is up to. Kishan, who belongs to the baniya caste of traders, is all about finances. He finds no respite from the wedding expenses to give Lachchi a loving look. “Phal, phool, gulaab jal,” he mutters throughout the time he is with her. Easily, this is not the Shah Rukh Khan I had signed up for. Yes, that version of the actor does surface. Romantic, compassionate, and respectful, he is everything that Lachchi desired. He is every bit of the Khan I wanted.

But, here lies the riddle (‘paheli’ in Hindi). The man, on whose side the leading lady and we are, is not a living being. He is a spirit. He takes any form – a bird, a plant, or a force of nature. The nameless being falls in love with Lachchi, at the very first sight. Are ghosts supposed to fall in love? Are their rules to their way of existence? We are not told.

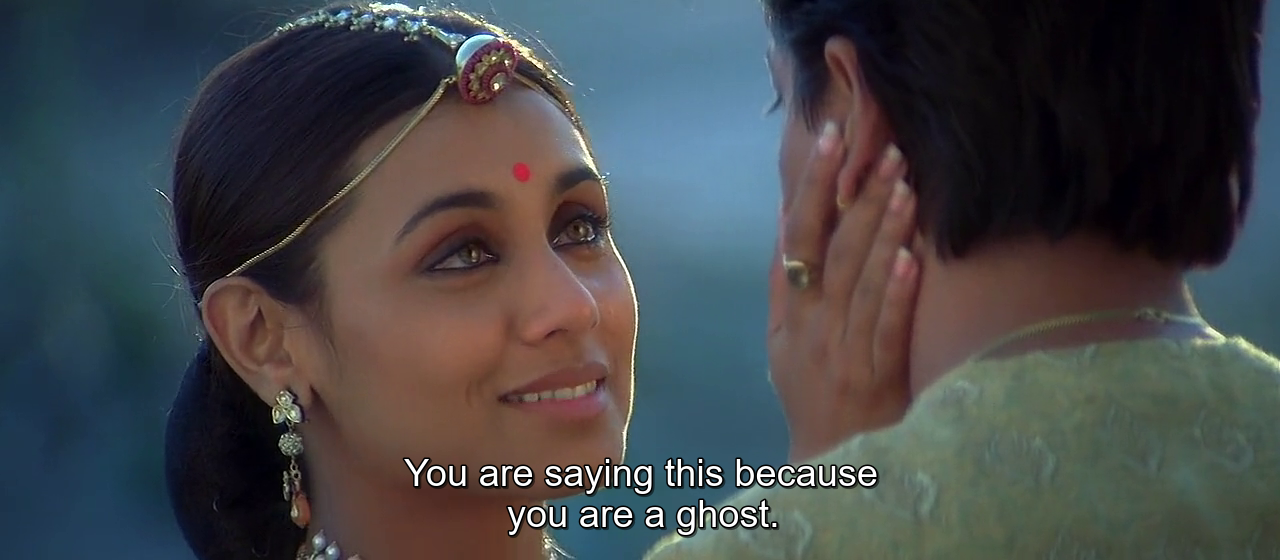

About Honesty in Relationships

The ghost does break some rules – at least one that would amount to impersonation in the real world. Yet, he makes sure the woman he loves knows his reality. There are no covers, no pretensions. The choice is entirely hers. Should Lachchi be subscribing to all the love that the masquerader showers on her? Or should she be waiting for her husband to return, half a decade later? Lachchi chooses the former. Delightfully enough, the screenplay makes no room to judge the woman for her decision. It is neither impulsive nor one in the desire for physical intimacy. It is the mind of a lonely, unloved woman at work.

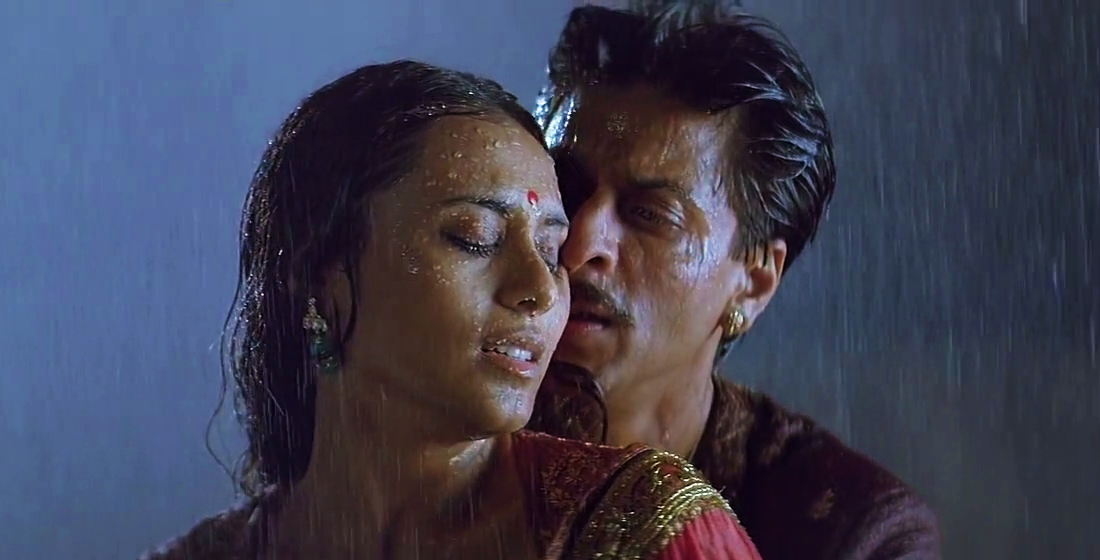

Mukerji and Khan’s Sensuous Chemistry

Rani Mukerji and Shah Rukh Khan are among Hindi cinema’s greatest romantic stars. Mukerji often marvels at her ability to romance even a tree on the screen. Khan’s trademark arm-spreading has become a nationally approved expression of love. Between each other, the duo has always generated unusually sensuous chemistry (Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, Chalte Chalte, Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna). Amol Palekar’s film is no exception. Make a note of this mushy love scene where he tells her what made him fall in love with her.

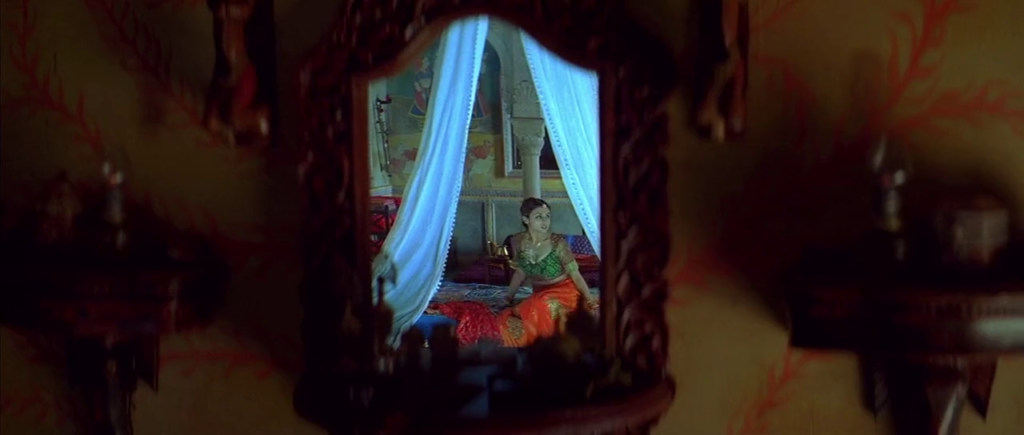

The steam quotient is further upped by a series of tender moments where Ravi K. Chandran’s camera lovingly caresses the actors thereby painting a life-like camaraderie. It is to be noted how the DOP lets shadows fall on the actors’ faces which, in turn, accentuates romance in key scenes.

When Berries and Puppets Become Striking Metaphors

En route to her husband’s home, Lachchi feels the urge to munch on berries she sees spots along the desert road. The kids fetch them and she gorges on them like a little girl. “Are they even meant for human beings? Animals eat them,” chides Kishan. The berries roll out of her palm. Her expressions change. Lachchi’s wish was for a husband to share the fruit with, not someone who would judge her choice.

The berries resurface in the third act when Kishan spots a woman eating them at his workplace. Perhaps the only relic that drives in a definite memory about his wife, he asks the woman to drop some for him. Kishan may not even like berries. It is just a memory – the nature of which he cannot make sense of. The berries roll down again, becoming a clear metaphor indicating how Lachchi is no longer his to share her favourite fruit with.

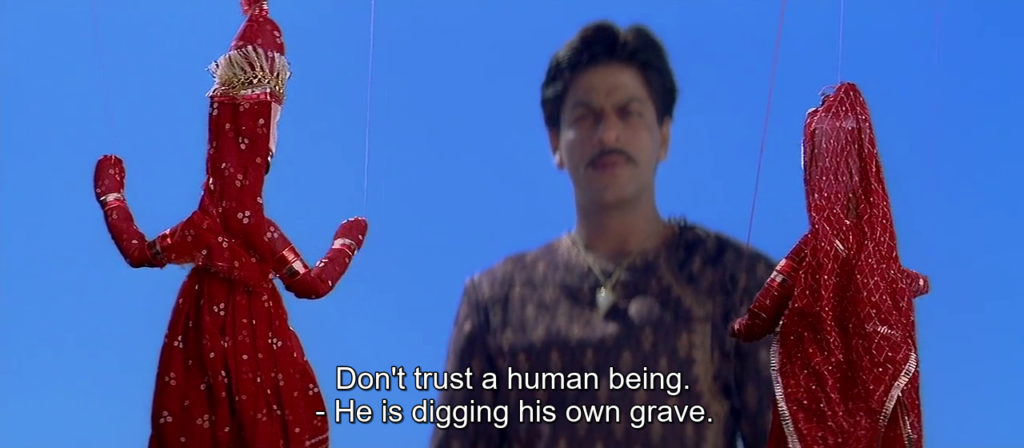

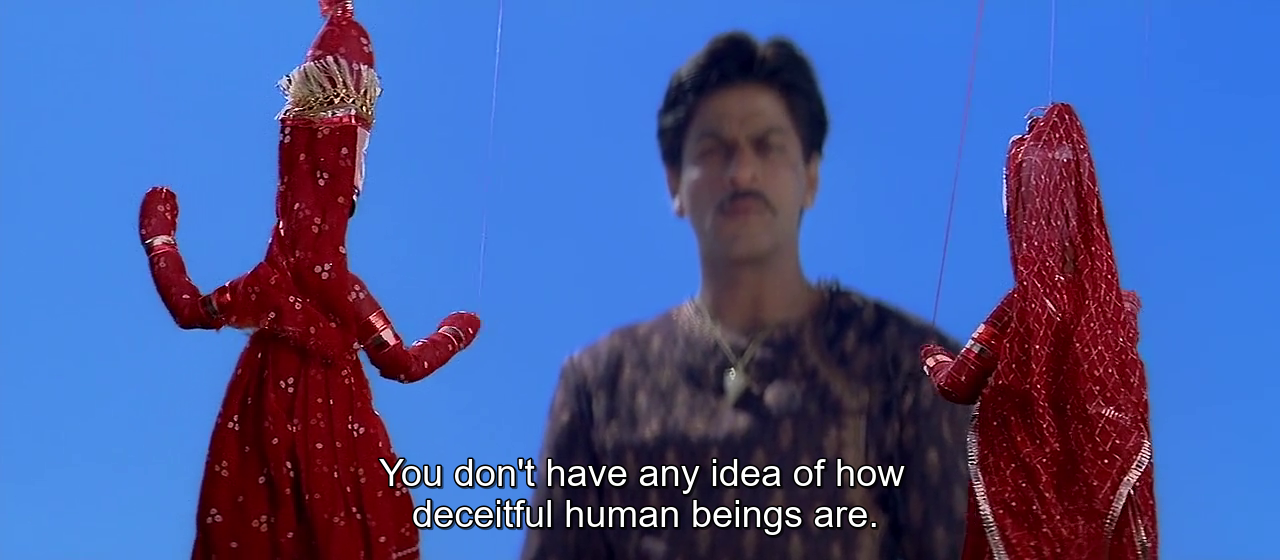

Then come the puppets. I am no fan of voiceovers in cinema. I always feel if a filmmaker establishes his story without supplementing his/her narrative with third parties, the better he/she is at the craft. Among rare exceptions is Amol Palekar’s Paheli which brings to us two Rajasthani puppets voiced by Ratna Pathak and Naseeruddin Shah. Designed as spirits who seem to know Khan’s spirit avatar inside-out, their bouncy storytelling is a class act. Palekar crafts their bit in the screenplay in such a way that they emerge as the leading man and the film’s conscience keepers.

MM Kreem-Gulzar’s Flavourful Songs

One of the greatest musicians to be working in Indian films today, MM Kreem’s name is slightly unusual to associate with a soundtrack that needs the authentic sound of Rajasthan. But, the brilliant composer from South India notches up a seven-course meal to satiate all those who appreciate earthy film music. The tunes dipped in folk flavours, are gorgeously cinematic.

Sonu Nigam and Shreya Ghoshal’s ‘Dhire Jalna’ is a powerful song that, in a quiet fashion, becomes the film’s emotional base. If ‘Laaga Re Jal Laaga’ is the celebratory number to fill our hearts with joy, ‘Kangana Re’ is a supple romantic number that stands out for its femininity – be it in the instrumentation or the lyrics.

Complementing MM Kreem’s creations perfectly are Gulzar’s words which open up a universe of progressive ideas. With the legendary wordsmith at the helm, it is impossible to imagine how the film occurred in a time period where patriarchy reigned supreme. Below is a passage from ‘Khaali Hai Tere Bina’ which I find heart-rending:

“Ek ek baat yaadi hai

Aadhi raat ki

Poore chaand ko

Jaagte hue bhi ho khwaab mein

Chehra ek hai

Leti hoon naam do

Reet ke teeno ki

Sunti hoon boliyan… yahaan!”

Technical Finesse to Bring a Folk Tale Alive

Paheli is a film involving a supernatural character. So, I was in for the editors (Amitabh Shukla, Steven H. Bernard) to have their tricks in place. Predictably enough, they employ a fade-out effect (with some neat VFX in place) in abundance. We see frames dissolve in moments of intense drama. Apart from that, Paheli is filled with the wipe effect which gives the illusion of reading a book – a folk tale – which is exactly what the film is based on. It only helps how Ravi K. Chandran’s camera knows when to move vigorously and when to quietly stay put. The sound design (Anuj Mathur, Baylon Fonseca, Anup Dev) is another department which is deserving of special mention. Despite having supernatural elements in its story, the sound team in Paheli refuses to incorporate the jaded whoosh and shimmer effects. In fact, the use of foley is astounding if we closely observe certain sequences – notably the camel race. Together with the dramatic original score (Aadesh Srivastava), Paheli ‘s sound department turns the film into a hugely immersive experience.

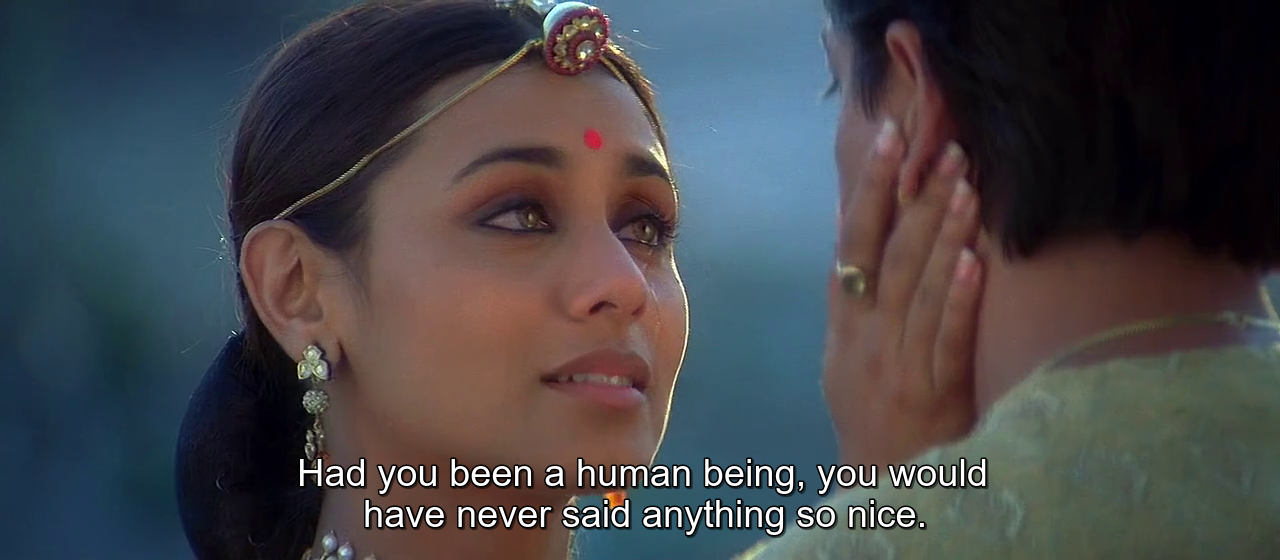

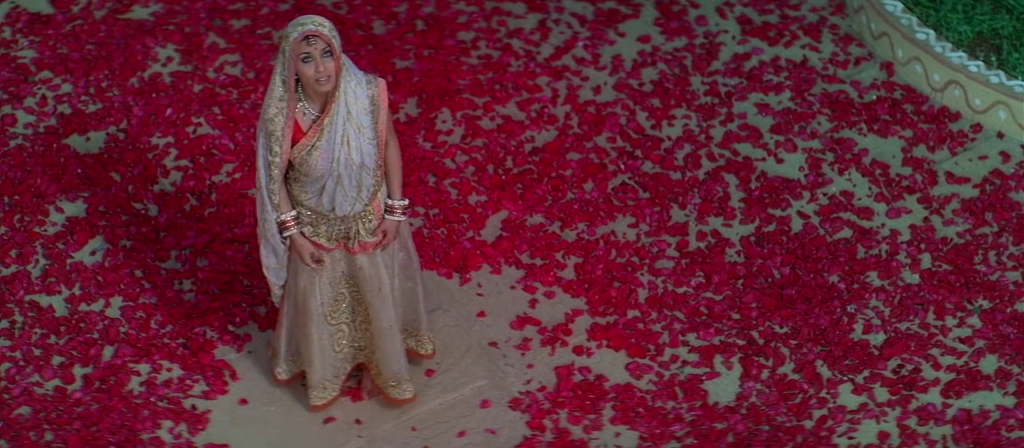

When the Camera Makes Love to Rani Mukerji

Ravi K. Chandran’s cinematography in Paheli is one that needs to be talked about separately. Given the way he photographs Rani Mukerji, I somewhere sense that her porcelain face is among the DOP’s absolute favourites. The frames, besides their jaw-dropping beauty, have their own unique tales to tell. I would also give it to the actor’s mettle to shapeshift but the ace cameraman’s ability to mould her as Lachchi lends gravitas to her transformation.

Mukerji is often shot well in her films – Ashok Mehta in Chalte Chalte, Thiru in Hey Ram, Amalendu Choudhary in Aiyyaa and Anil Mehta in Saathiya to name a few others. In Paheli, it is evident how Ravi K. Chandran deconstructs her appeal in a mode staggeringly different from their previous collaboration, Yuva. Rani Mukerji’s face becomes his canvas and the frames below become ample proof.

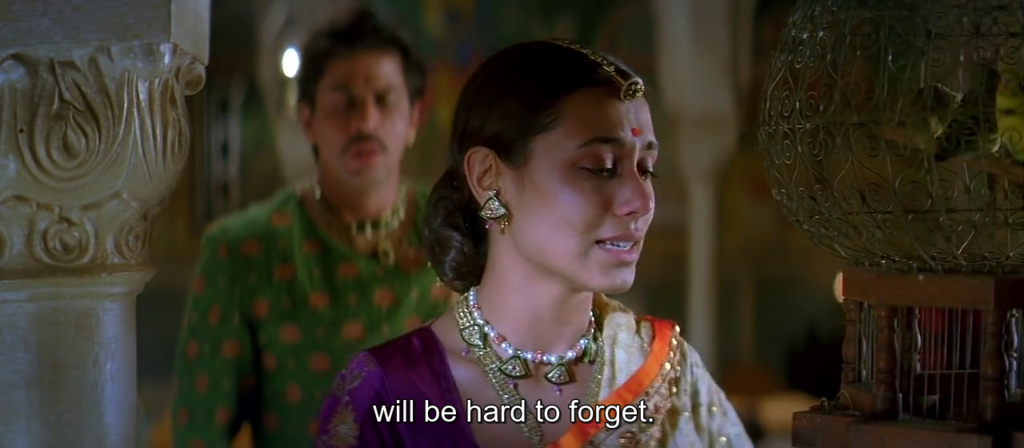

Because Women’s Empowerment is a Real Deal

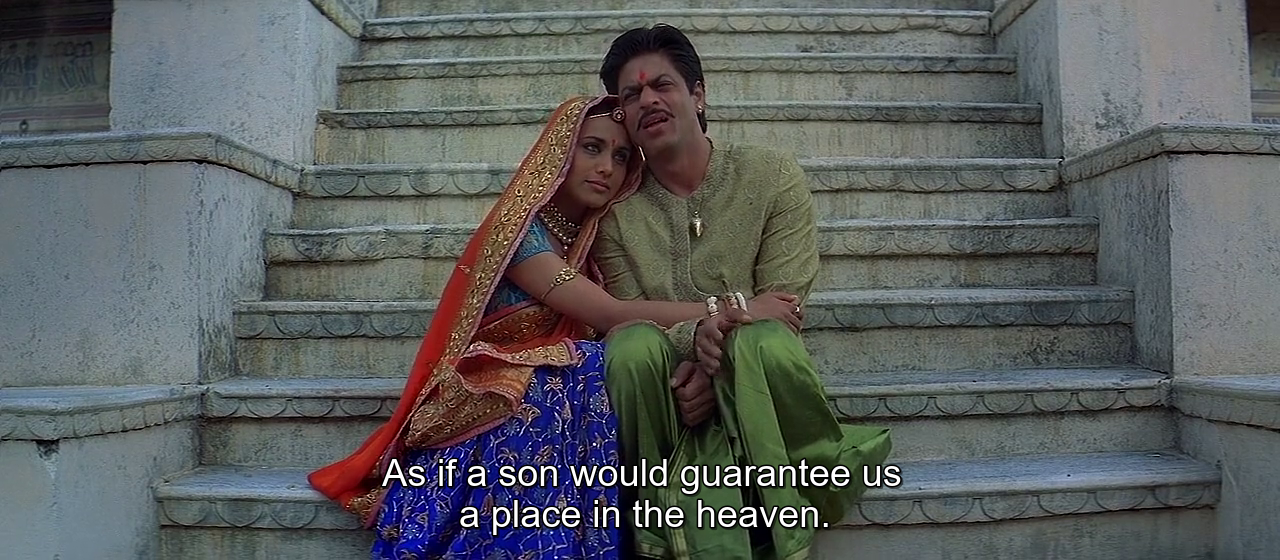

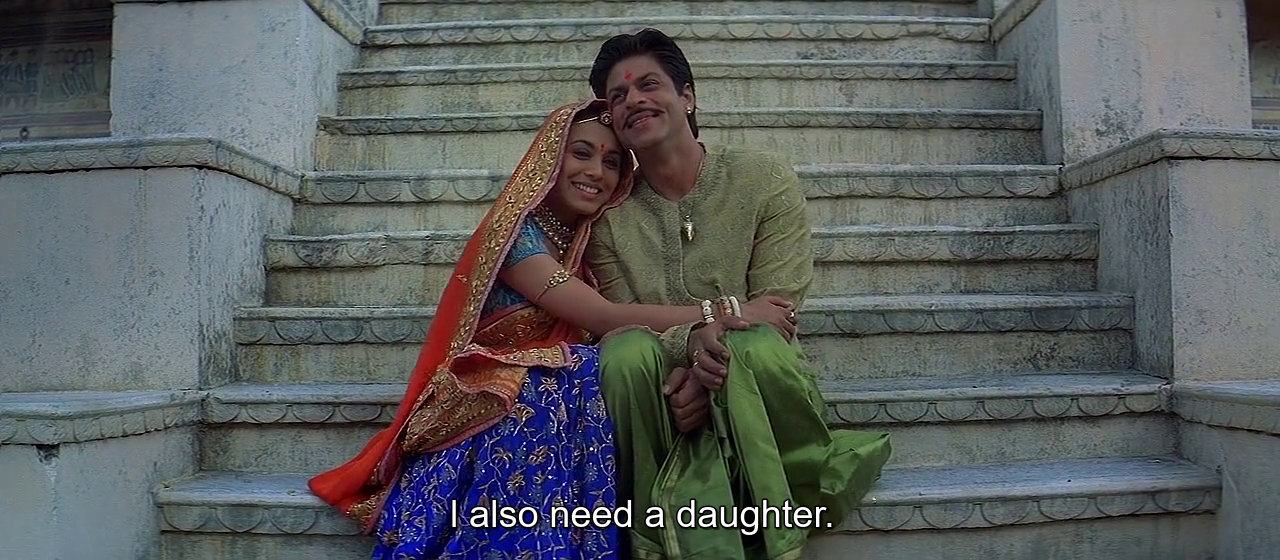

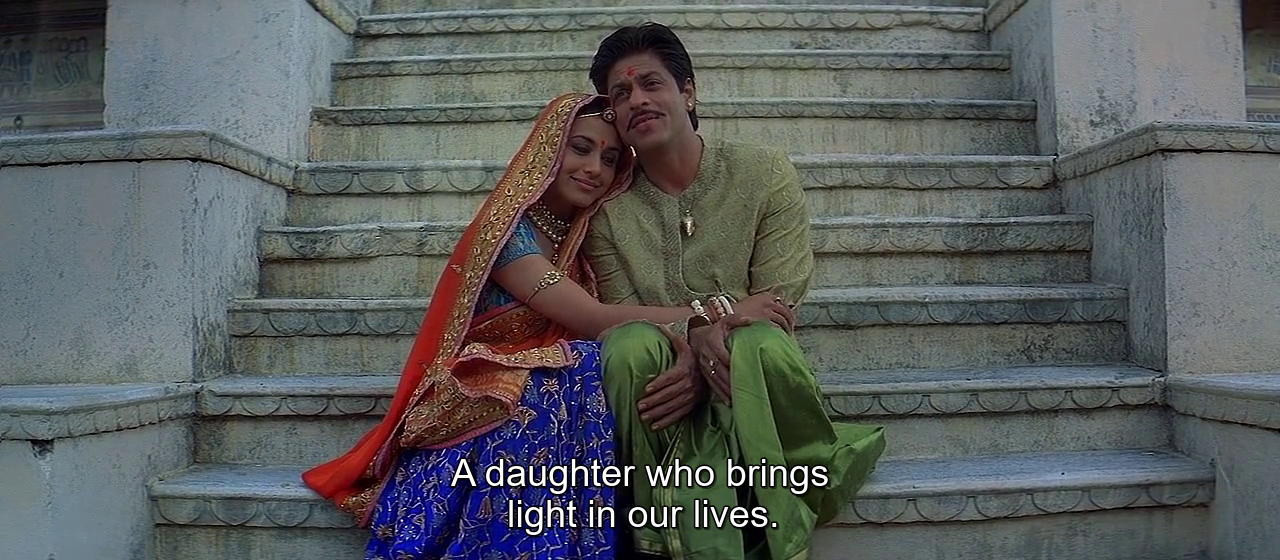

Based on Vijayadan Detha’s short story ‘Duvidha’, Paheli is an authoritative woman empowerment tale. It does not pay heed to rules dictated by an era, a region or a religion. It boldly and sensitively addresses the plight of women who choose to suffer in silence. The film is also about a man who does not devalue a woman for her gender. In an intimate moment, Kishan and Lachchi make a wish for their baby.

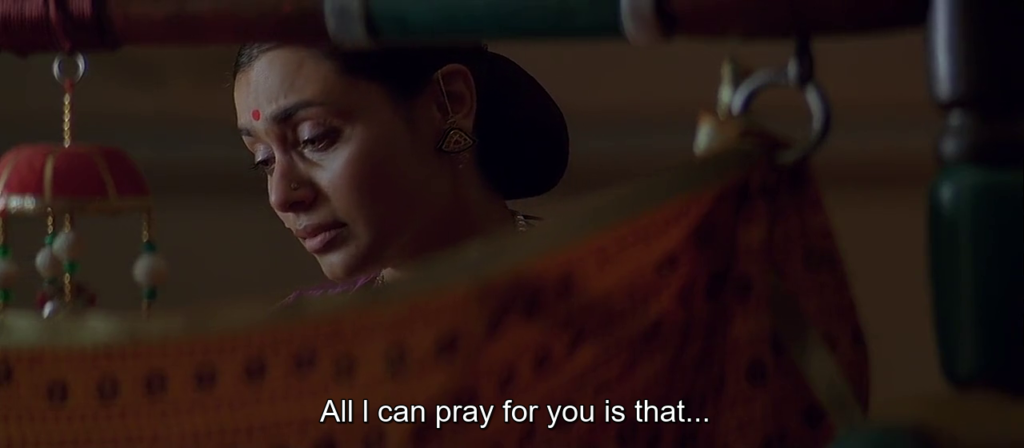

Lachchi’s wish for her daughter, after she is born, is also about the girl having agency over her choices when she grows up.

This way, Amol Palekar’s film keeps its female lead at a higher moral citadel making it easy for us to empathize with her. Paheli’s feminism is not one that shouts off the rooftops. It gently, and fiercely questions male privilege while also spinning an elegant folk tale around the concept. So much so that I really do not mind a sequel to this pleasant Khan-Mukerji romance.

Paheli is now streaming on Netflix.

ALSO READ: ‘Jodhaa Akbar’: Chronicling the Original Power Couple