Kolkata based love stories make me go weak in the knees. Be it the ones penned by Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay (Devdas, Parineeta) or others like Raincoat and Meri Pyaari Bindu, a lot of them paint childhood love on celluloid with remarkable beauty. Now, there exists no bigger literary piece on this theme than Devdas, that’s been celebrated by almost all film making industries in India.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s version of the story – that released in 2002 – remains special for umpteen reasons. The first film I ever purchased a VCD of, Devdas was seen until every frame was imprinted in my mind and every line by-hearted.

On its anniversary, here I list a set of observations I make as I revisit it today:

Bhansali’s tryst with opulence

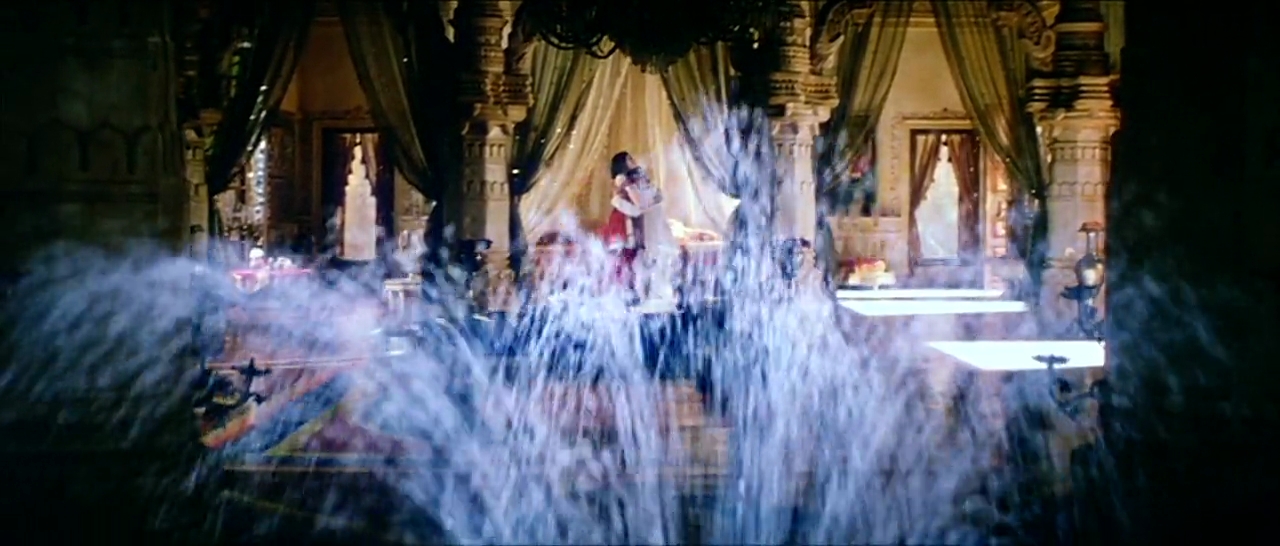

The most expensive Hindi film of 2002, Devdas is where the director famously discovered his penchant for custom-made sets. If you have seen other versions of the same story, each of them flourished with exterior shots. Bhansali’s version has about 5 odd moments in daylight, the most significant one being the finale.

For the rest, the film comfortably rests in four exquisitely designed palaces – one for each protagonist. Paro’s mansion is comparatively modest, filled with glass doors, making her emotions look all the more transparent. Interiors of her in-laws’ palace are spacious, projecting the emptiness in their lives with the absence of a thakurain. Devdas lives in a busy mansion that more or less resembles a big Gujarati joint family than Bengali with annoying, calculative members. Chandramukhi’s kotha is never really explored in entirety. High on architecture with defined trails for elaborate dance numbers, the tapestries and staircases are made to look extra-luscious with incandescent lighting.

It is also disappointing how Bhansali landscapes his film entirely in artificial lights, especially given the fact that the dialogues vividly describe Paro and Devdas’s meetups in the guava orchard.

Sandesh, an excuse!

For a non-Bengali, Sandesh translates to a ‘message’. And with the way Sumitra and Paro bring it to their rich neighbour’s place, we felt as if it is something religious and sacred. Not that the women never open the thali and share its contents. It is only later that I learnt it is a Bengali dessert made out of milk.

Commoditizing the unmarried girl

Paro is perhaps the most stunning woman you will ever set eyes on. Educated and wise, Devdas as a literary work asserts how imperative her impending wedding is. Her less-privileged parents are concerned whether she will be accepted in a wealthy household. Paro’s marital eligibility is the film’s locus, eventually leading her mother to make a selfish decision – Paro will be married off to richer family than Devdas’. The idea is not about a mother taking a vow. It is in the way she centres it on affluence rather than on her child’s happiness.

When Sumitra pays a visit to Kaushalya on Kumud’s god-bharai, she wishes for a son. Later as things crumble to bitterness, she curses, “May your home be filled with moonlight. May your family have a daughter,” The tone is that of a jinx – how a girl child can harden lives. In an earlier scene, Kumud is offered tonnes of jewellery. The family matriarch declares, “Tum hamein beta dogi, aur hum tumhe kuch na de?”

Men are no less douches in Chattopadhyay’s world. Devdas is forever condescending towards Chandramukhi, despite his propensity to reach out to her in moments of insecurity. Despite explaining her feelings at various junctures, Chandramukhi’s irrational likening to Devdas stands unexplained. Of course, he looked hot in designer dhoti kurtas. Was that all for her?

Dances and tonnes of melodrama…

Not a part of the original literary work, Morey Piya and Dola Re make for exquisite music videos – especially the former. One that cuts between a mother’s angst-ridden solo performance to a couple’s lyrical lovemaking by the lakeside, More Piya takes us through diverse emotions. It only adds to the impact that the succeeding portions seep in high voltage drama and a major plot twist.

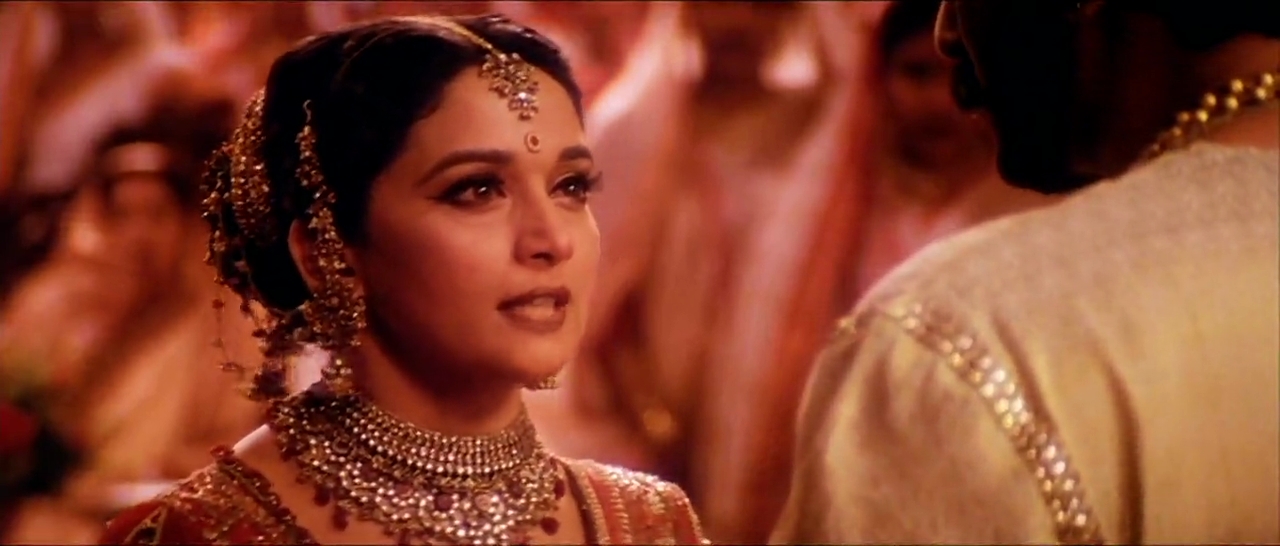

Dola Re is more of an excuse to see two of Bollywood’s finest danseuses perform. They do that to perfection with coordinated clothes, jewellery and Saroj Khan’s firebrand moves. The scene later attempts to throw in a women empowerment angle, which largely appears forced despite Madhuri Dixit lending thrust and gravitas to the material on papers.

‘Silsila Yeh Chahat Ka’ featuring a luminous Aishwarya Rai is notable for Shreya Ghoshal’s grand entry to our playlists. The number is also tastefully choreographed (Vaibhavi Merchant) with an unusual prop – a lamp – and a group of women trying to extinguish it.

The mujras ‘Kaahe Chhed Mohe’ and ‘Maar Daala’ are amongst the bests in the genre and given Dixit’s proficiency at the craft and Ismail Darbar-Nusrat Badr’s stupendous musical pieces, we are in for a treat.

Words of wisdom!

“Itna ghuroor, to chand ko bhi nahin…

Kaise karta woh ghuroor? Us chand par daag jo hai!”

“Jo cheez apni ho, use maangne mein lajja kaisi?”

“Khona to har haal mein hai Dev. Ya tumhare saath, ya tumhare bagair!”

“Diya tum jalati thi, par jalta to main hi tha…”

“Har dukh aanewali sukh ki chitthi hoti hai Dev babu. Aur har nuksaan, honewale faayde ka ishaara…”

“Jo shama mehfil sajati hai, kareeb jaane par wo jala bhi sakti hai…”

“Kaun kambakht bardasht karne ko peeta hai?”

“Tawaif ki aangan ki mitti milakar hi Durga ki moorti ubharti hai. Aur wo mitti itni kamzor nahi…”

“Babuji ne kaha gaon chod do, sab ne kaha Paro ko chhod do, Paro ne kaha sharaab chod do, aaj tumne keh diya haveli chhod do. Ek din aayega jab wo kahenge duniya hi chhod do…”

“Aur pehla pyar to umr ki farak ki tarah hota hai, jisse chahkar bhi nahi mita sakte…”

“Dekho… us jalte hue diye ki roshni mein hai Dev babu. Us bistar ki silvaton mein bhi. Us adhoori pemane se aaj bhi chalak raha hai Dev babu ki pyaas. Aaj bhi mehak raha hai ye karma unki khushboo se. Agar le jaa sakti hai to le jao, ye roshni, ye silvatein, ye khushboo sab…”

The breakup song of our times…

Before it became fashionable to portray couples that stray, matrimony pretty much sealed the deal – in mainstream cinema, populist literature and other works of fiction. Devdas features one of the most poignant breakup songs of its times – ‘Hamesha Tumko Chaha’ that is filled with heart-breaking visuals and equally pensive lyrics.

“Woh bachpan ki yaadein woh rishte woh naate woh sawan ke jhule

Woh hasna woh hasana woh rooth kar phir manana

Woh har ek pal mein dil mein samayi diye mein jalaye

Le ja rahi hoon

Main le ja rahi hoon…”

Performances – Good, bad and the ugly!

Besides Kirron Kher’s Sumitra and Devdas’s affectionate Badi Maa, Bhansali was in no mood to give pure Bengali textures to his characters. There is a sprinkled dose of Bengali interspersed in dialogues but the actors speak in disparate dialects.

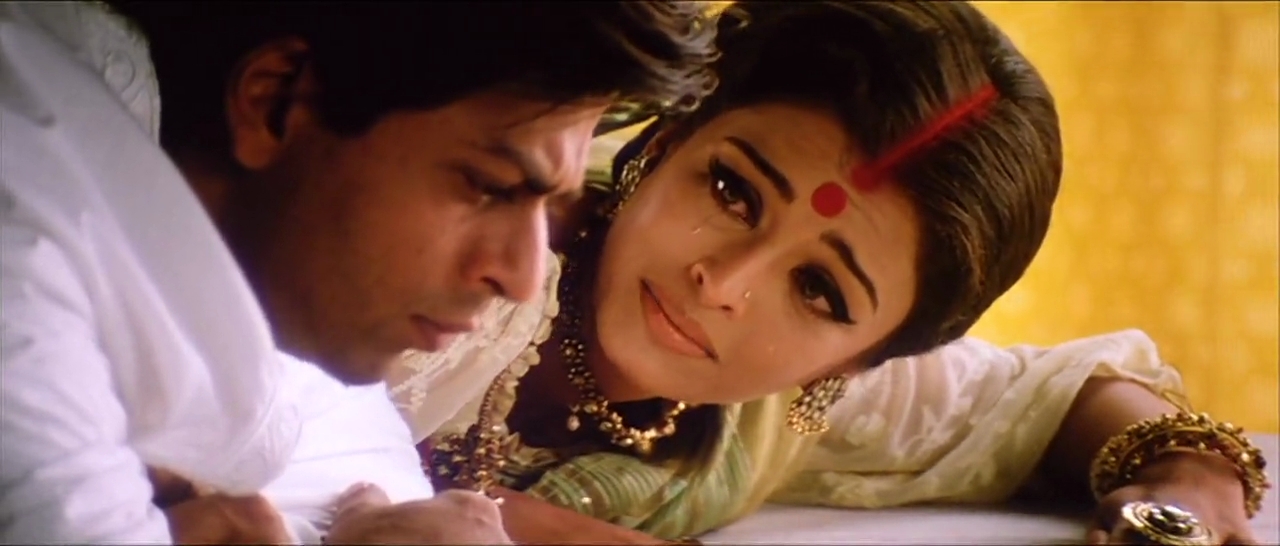

However, that doesn’t take away any bit of the appeal from some of the shimmering performances in the film. Taking the cake here is Aishwarya Rai who stuns us with that magnetic presence of hers. Not known for her histrionic abilities, Rai makes full use of the opportunity and internalizes a role that seems tailor-made for her.

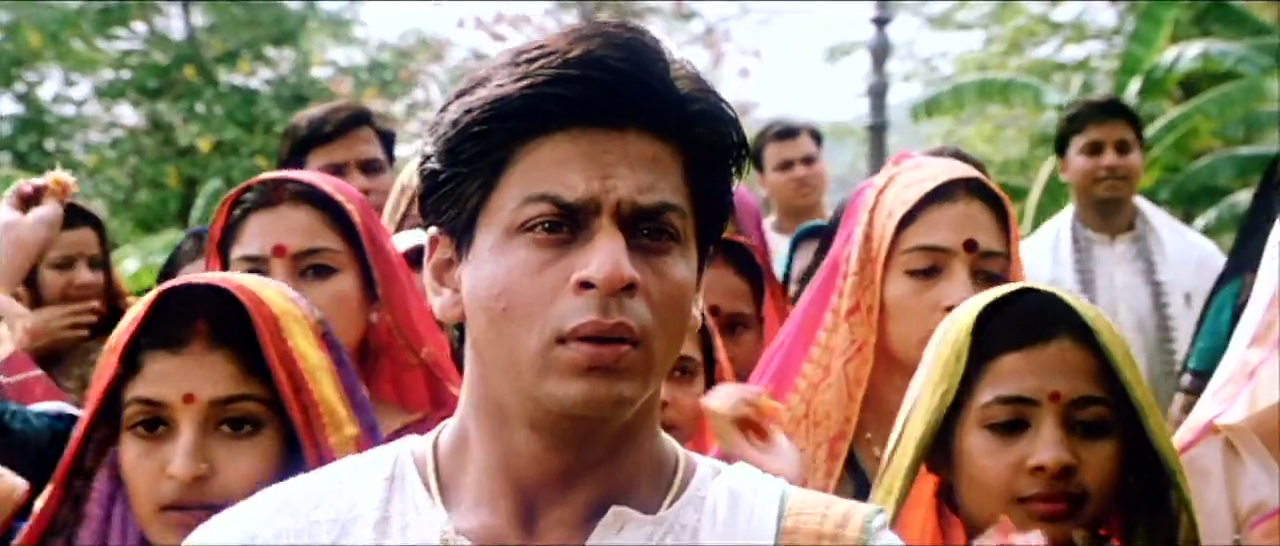

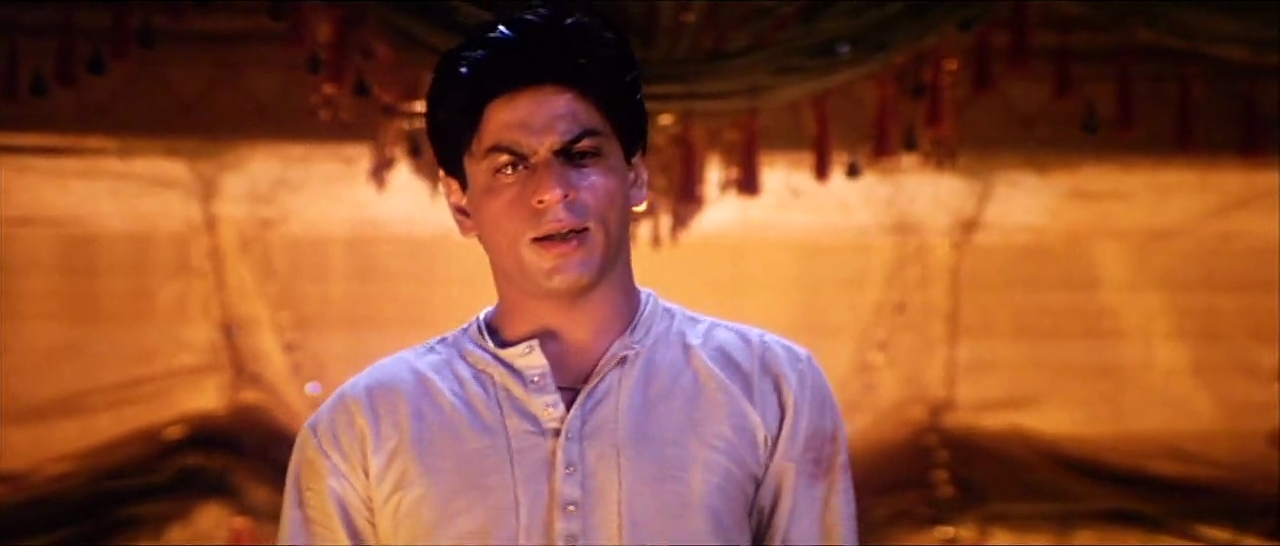

Given her vocation, the film doesn’t wield the need for Madhuri Dixit’s Chandramukhi to project Bengali traits. The actor is adept at getting the sophisticated mannerisms of a classy courtesan from Kolkata’s Chitpur area. With reactions and terrific dramatic intonations in dialogue delivery, Devdas is one relatively measured performances in her a career that’s not exactly filled with bravura acts. With women stealing all thunder, Shah Rukh Khan is no less as the lead man, and he totally knocks it out of the park in moments of insecurity and false pride.

Kirron Kher as Sumitra shines in a sharp supporting role that offers her tremendous scope to express emotions manifold. Ananya Khare does well in a stereotypical evil bhabhi part while Smita Jaykar and Manoj Joshi are terribly miscast. However, no actor in Devdas is as exasperating as Jackie Shroff who plays the flamboyant, word-play loving Chunnilal.

The untold story of Devdas and Chandramukhi

Much has been said about Devdas’s desire for Paro. On how she is the human form of love and how she resembles a river and a gorgeous doe. Chandramukhi never gets her due in her liaison with Devdas. Even Paro declares, “Tawaif ki taqdeer mein shohar nahi hoti…”

This is as we realize that somewhere deep down Chandramukhi craves for spousal love. From a man who wouldn’t objectify her.

Given her low status in the society, Devdas clearly holds the upper hand here and, hence, is also the decision-maker in this ‘arrangement’. When he finally confesses love, there ensue a few minutes of magical chemistry.

“Aur tumse koi pyaar nahi karta, sivaaye mere…”

“Aur marne ke baad agar bhent hui, tumse alag nahi reh paunga…”

His kind of women!

Devdas has his characteristic ways. Foreign returned and a law graduate, he had a refined taste of everything. One who falls asleep with his cufflinks on, the man knew the kind of women he needed – bearing a fine balance of beauty, mischief and sass. Something that Paro was the benchmark for. A feat that Chandramukhi attempted to accomplish.

Despite their differences, Paro and Chandramukhi patched similarity in multiple ways, forming the kind of women Devdas longed for. In a love story that drew inspiration from the Krishna-Radha-Meera tale (minus self-destruction), the women in Devdas are notable for their resilience. While they have no means to challenge social diktats, these women stand tall in their immediate personal relationships. They are strong and have their ways with perverts and traditionalists. Beyond a point, they do not let others dictate terms for them. And finally, both women have their own reasons to love Devdas and they do not feel obligated to explain the same to anyone. Further, on a lighten vein, both seem to enjoy a good game of cards! Atta girls!

The Bhansali difference…

It was Devdas that sort of laid foundation to what we call SLB cinema today. Marked by luxurious sets, elaborate costumes and jewellery that even project character arcs in a subtle way, Bhansali also involves crystal clear metaphors that are further explained through song lyrics. For instance, the diya and the mark on Paro’s forehead are of significance in Devdas.

Bhansali also experiments with multi-camera setups, making full use of space in his frames. We see his heroine run to get a glimpse of her man, adding great drama to the proceedings.

Bhansali’s songs, as mentioned earlier, are poetic yet extensions of his dialogues. The characters make no bones to etch out their emotions in plaintive terms. The direct communication works at times, wavers at others. Also appreciable is how the film stays true to its musical narrative. If you notice, most dialogues follow a rhythm pattern in Devdas. Most notably when the young Paro laments as Devdas leaves for London.

The lack of natural light in Devdas, for instance, attempts to drown the relatability quotient. This isn’t a historical romance, for starters. Set in an era that is almost nine decades older, the film steers clear from politics. Characters live in their wonderland of great luxury and emotional tribulations while paying no heed to the larger developments in the society during that period.

Having said that, it is heartening to realize how Devdas remains fresh to date. Although slightly underwhelming compared to Bimal Roy’s version of the same story, this epic retelling couldn’t have been any different – especially from a commercial standpoint. Devdas, Paro and Chandramukhi will remain entrenched in our millennial minds for years to come, as the film seems to age like fine wine.

ALSO READ: Bhansali’s Women – A Heady Mix of Dignity, Bravado, and All Things Elegant