How often do we come across cinema that is meditative with a uniquely fluid storytelling method at use? The fluidity I am referring to is with respect to the way the screenplay evolves, balancing one element with another while also translating its rather odd structure to screen with remarkable conviction. Veteran filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar in his latest film Pain and Glory (Dolor y gloria) marks a feat by astutely projecting his lead character’s emotional metamorphosis – right from his childhood until old age with meticulous textures.

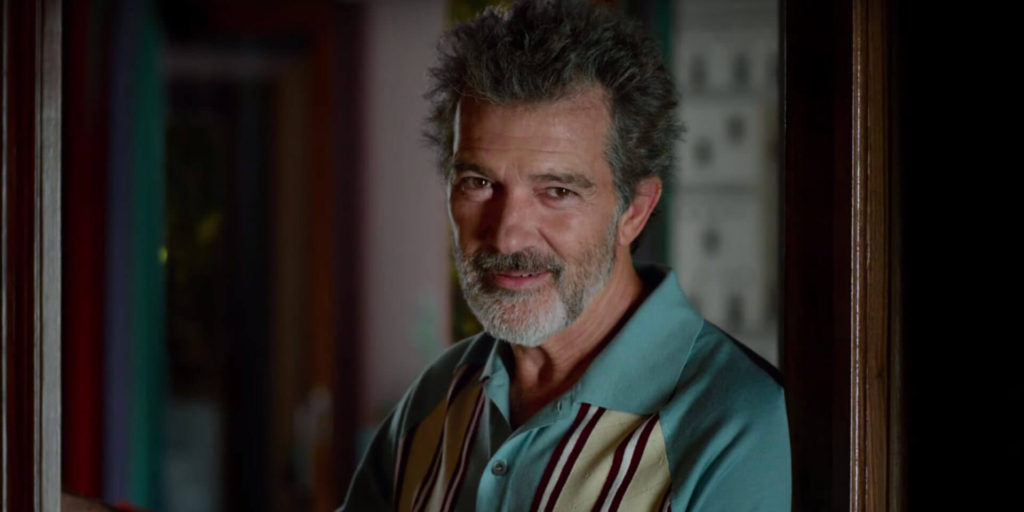

One that runs in flashbacks which do not specifically focus on any of the said periods, Pain and Glory is about Salvador Mallo (Antonio Banderas), an ageing filmmaker who is way past his heydays. Interspersed with brief yet concrete dollops from Salvador’s childhood in a remote Spanish village, the initial chapter focusses on his reconciliation effort with his estranged lead actor Alberto (Asier Etxeandia). This episode also sees Salvador diving into substance abuse. There is another tiny yet mesmerizing passage where he accidentally reunites with his yesteryear lover Federico (Leonardo Sbaraglia) which becomes a window to revealing Salvador’s homosexual identity. Taking us sinuously back to his childhood, Almodóvar also fleetingly projects the very instance where a young Salvador realizes his sexual affinity for men. It is not the most telling of scenes but the writing cleverly leaves it to the viewer to interpret.

Pain and Glory, with its intricate layers and episodes panning through decades, is ultimately a fine character study. We delve deep into the mind space of a man who is slowly plunging into professional irrelevance. We also feel the regret in him for not having fulfilled his industrious mother’s last wish. There is a finite yet delectable taste of lost love. And last but not the least, Salvador’s passionless yet need-oriented equation with Mercedes (Nora Navas) gets its share of focus. Almodóvar makes sure that none of these chapters is overly expository. The stories – singularly and collectively – feel personal but their screen duration on papers together with the way they’re weaved by the editor is perfectly in tune.

Talking about the film’s intensely autobiographic demeanour, Pain and Glory feels like a gorgeous mélange of memories. Now memories are not always recollected in the order of their occurrences – which explains the film’s unsystematic narrative oscillations. Be it the rural lifestyle in 1960s’ Spain or in the way physical ailments make way to solitude and agony, one sees several subtexts in the screenplay that might have actually been lived through.

Acing the central part of Salvador with life-like assuredness is Antonio Banderas whose vulnerable eyes and fidgety body language catapult Pain and Glory to realms of absolute excellence. Be it with his brief yet hazardous encounters with drug peddlers or in the way he communicates icily with his elderly mother, the actor packs in several emotions through the film’s decidedly lethargic pace. Penélope Cruz is delightful in a small part which also seems tailor-made. Cruz’s portions reminded me of the equation she shared with Carmen Maura in Almodóvar’s 2006 gem Volver. Asier Etxeandia is well-cast as one of the important catalysts in the plot whereas Leonardo Sbaraglia makes a striking impression in a rather minuscule part.

ALSO READ: 30 World Cinema Titles from 2019 That Must Not Be Missed

The photography (José Luis Alcaine) comes with a definite sharpness, allowing an easy mixture of close-ups and bright-hued frames to co-exist with great beauty. That way, Pain and Glory is extremely colourful, as if it were to compromise for the dullness that loomed large in Salvador’s life. The original score (Alberto Iglesias) is suitably moody as it vacillates tastefully along with the central character’s complex mindscapes.

Staged in a film set, the film’s clever finale only reminds us that Almodóvar is one amongst our cinema greats for a reason. Pain and Glory lends dignity to heartbreaks and unpleasant revelations. It makes reconciliations look organic and graceful. It is unflinchingly real to see the once-celebrated leading man dabble through physical and mental infirmities, like any other ordinary person. It is quietly affecting to see him subscribe to temporary respites, not acknowledging the actual vacuum within. Through each of these nuances, Pain and Glory proves that Almodóvar, for sure, knows his universe. He has certainly mastered the technique of making his viewers immerse in his stories and emerge with their eyes drenched, even though his characters seldom do. Not a commonplace skill that is, I must add.

Rating: ★★★★