“Jamini, Jamini…” Calls out her mother in a frail yet demanding tone. This shout is one of the most haunting ones I have ever heard in Hindi cinema. There’s a lot to do with the actor’s (Gita Sen) tenor and vocal quality but it is also about the fact that Jamini is an unusual name for a Hindi film heroine. With a name that translates to ‘night’, Jamini (Shabana Azmi, amazingly restrained) lives a placid life in a corner of a dilapidated mansion that was once a hallmark of the absolute gentry. Mrinal Sen, in one of his rare Hindi films, paints an intense picture of stillness, longing and abandonment in his splendidly photographed (KK Mahajan) and thoughtfully titled Khandhar.

Still in her youth, Jamini’s existence might not be unusual for that time and era. Tending to a bed-ridden mother, life seems to have crippled her ostensibly vivacious spirit. At one point, we fathom how Jamini has stopped making her own memories. Stuck in the khandhar by the side of a tiny pond and a temple, her only window to the world might be books and a few letters from her sibling. In her eyes, we see a firm eagerness that seldom reaches out to her actions. It is as if she has capitulated to fate and not without an air of regret on her face. In a breakdown towards the end, she pleads to her arduous mother, “Mujhe samajhne ki koshish karo, Maa,” and we almost cry with her.

Is Khandhar a love story? In rulebook terms, we do not witness the male protagonist “enter” Jamini’s life. In a chance encounter, Subhash (Naseeruddin Shah) merely brushes off her life. He mutters a reassuring ‘yes’ in a vulnerable moment. We expect sparks to fly and the story to take familiar contours of a prospective romance. However, the story is way too aware of its condemned existence to spin any such miracle. An atmosphere of inadequacy looms large preventing any of the protagonists from taking actions that will make a difference to another. Also with Khandhar being a story with Jamini as the pivot, we wonder if there existed an equally profound backstory of Subhash.

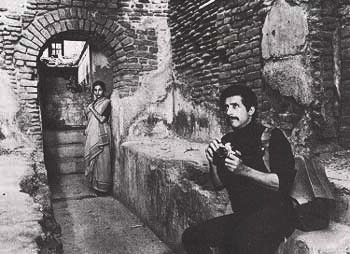

A passionate still photographer, it is Subhash’s studio room that opens the film to us. Tranced in a reflective mood, Subhash is in process of developing a handful of images that he clicked from a place that he describes to have slept off while narrating its own story. Soon we are taken to a brief flashback wherein his friend Dipu (Pankaj Kapoor) turns up with an invitation to his native village mansion that is not in the best of shape today. Far off from the bustling city crowd, Dipu announces the place as a ‘Photographer’s Paradise’ and an experience worth having. Upon visiting the barely inhabitable bastion infested by mosquitos and owls, Subhash’s uneasiness is soothed by the visuals around.

The first striking sight being that of Jamini, whom he spots from the terrace, looking out of her bedroom window. One must also notice Mrinal Sen’s striking camera placements and his actors’ gaze that is telling in nature and also in absence of too many words. Even Subhash’s presence comes with an aura of smoulder, a certain unstated suavity that handsomely contrasts with Jamini’s simplicity and mature grace køb viagra. Their interactions marked with minimal conversations are so delicately sensual that it also underlines Azmi and Shah’s sizzling chemistry besides Sen’s directorial brilliance.

ALSO READ: ‘Sparsh’: A Classic ’80s Romance Garnished With Chemistry and Simplicity

Albeit plainly dressed in colourless sarees (draped mostly in Bengali style) and shawls, Jamini’s effervescence begins at her glistening eyes. Described aptly by Dipu’s friend Anil (Annu Kapoor) as ‘shamshan champa’, Jamini’s reticent demeanour and expressive body language make us believe how there is more to her than what we see. Intelligence is one aspect that comes out and also accurately stated by Subhash as he talks to Dipu. Beyond that, there is a mystique in her that makes us want to know more about her.

Jamini’s bond with her ailing mother is another strong leg to the story. It is particularly affecting when the mother quizzes if she’s wearing the dotted blue saree, which looks great on her. Jamini lies to her that she is wearing a blue shade but not one with dots that had got tattered long back. This could also be interpreted as Jamini’s own resigned dreams which might want to bloom yet again. Besides the central plot that has shades of romance and domestic drama, one can’t miss the director’s politics as he briefly mentions the abolishment of zamindari and the plight of the working class.

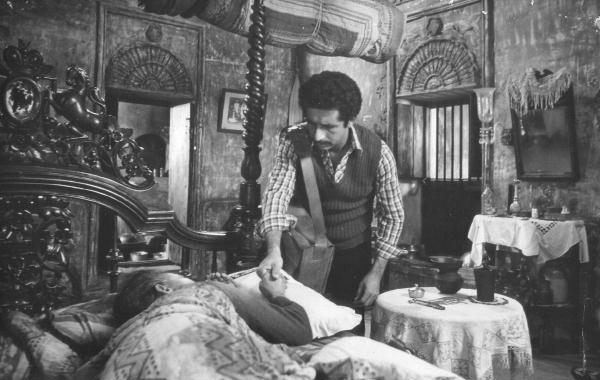

It is also stimulating when a central character in a film never turns up physically. In Khandhar, Niranjan’s presence or the lack of it is largely highlighted with a decent dose of theatrics. Forming an element of another heartrending episode in Jamini’s life, the man is a distant relative who is omnipresent in the film as a ray of hope to the ailing mother. And Subhash? Well, we spot him glaring at a magnificent oil painting and imagine the visual of an adorned Jamini in a chandelier-lit hall. The unanswered question is whether he was in love Jamini or with the extremely photographable sight that she was. Perhaps all he wanted was a resounding portrait of Jamini, that he eventually manages to capture with the antiquated ruins lending the backdrop. Only at the cost of us believe how he could have been her future, the Niranjan who returned one fine day…

Khandhar can be viewed on YouTube.