In a rather catastrophic year that left filmmakers high and dry whereas film lovers awaited a handful of titles to quench their thirst, film (as a medium) was predicted to disappoint. Qualitatively or otherwise, that certainly was not the case with film in 2020. Even though theatrical releases were stalled for a good part of the year, the inflow of great cinema at film festivals and streaming platforms did not stop. Interestingly, unlike the previous years, the Top 30 is dominated by films from the United States of America. Here are the best films of 2020, in reverse order:

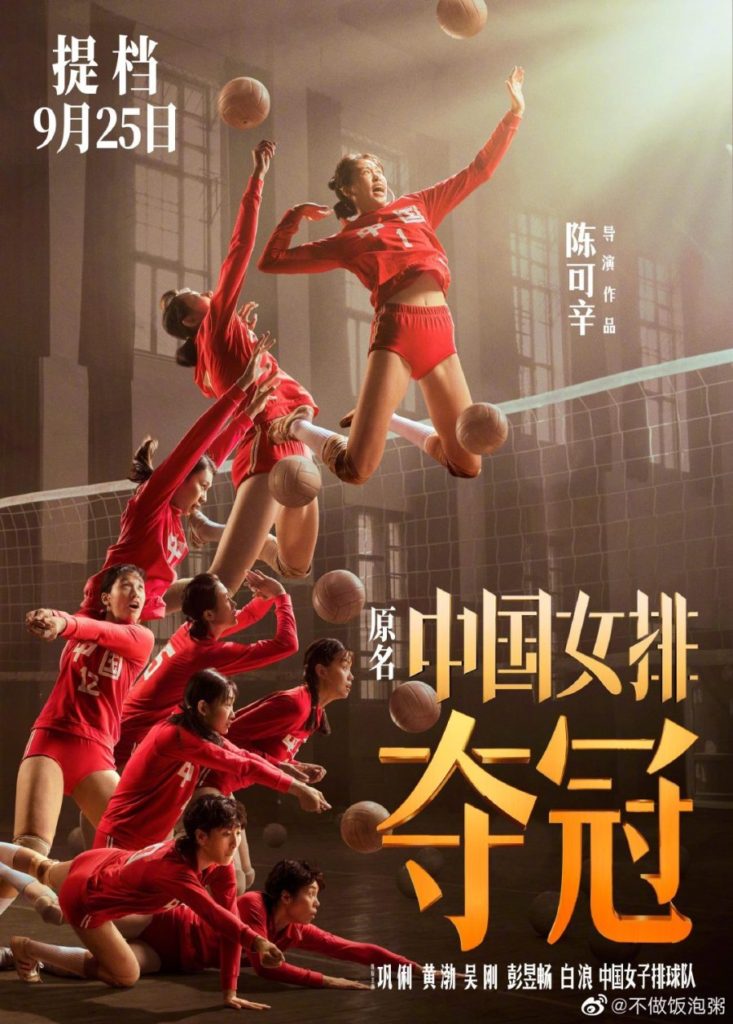

30. Leap (China)

China’s official entry to the 93rd Academy Awards is a sports film. The sport in question is women’s volleyball. Not only that, the film helmed by Peter Ho-Sun Chan is one that chronicles the sports career of ace player-turned-coach Lang Ping. High on patriotism, the film rarely becomes a deep study of its subject. The presentation is showy which helps a great deal in keeping us engaged along with its not-so-short runtime. The matches are impressively staged whereas the actors who appear as players (including Bai Lang in the lead) are astutely involved in the process. So much so that the realism emanating from Chan’s (rather) safe fare is worth noticing. Leap is also an underdog victory tale that does not take the full shape it ought to have but the film, broadly, is a very convincing entertainer.

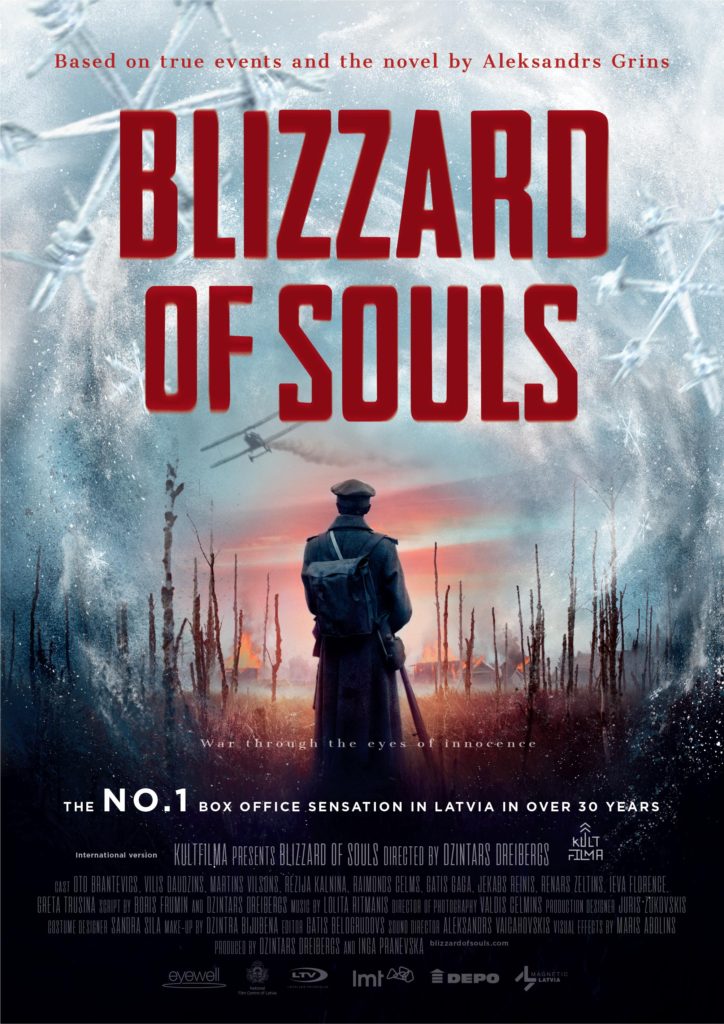

29. Blizzard of Souls (Latvia)

A huge commercial success in Latvia, Blizzard of Souls narrates the distressing first-person account of a teenage soldier during World War I. Adapted from Latvian writer Aleksandrs Grins’ book by the same name, Dzintars Dreibergs is a coming-of-age saga whose setup is reminiscent of 2019’s celebrated war drama 1917. However, the similarities end there as Dreibergs’ film delves way deeper into its patriotic spirit as compared to the aforementioned American film. Blizzard of Souls meticulously projects the 1919 Battle of Cēsis fought by cadets who were underaged, troubled souls. With a final act that is terrific in every sense of the word, this technically sound film is headlined by a confident lead act by the sensational debutant Oto Brantevics.

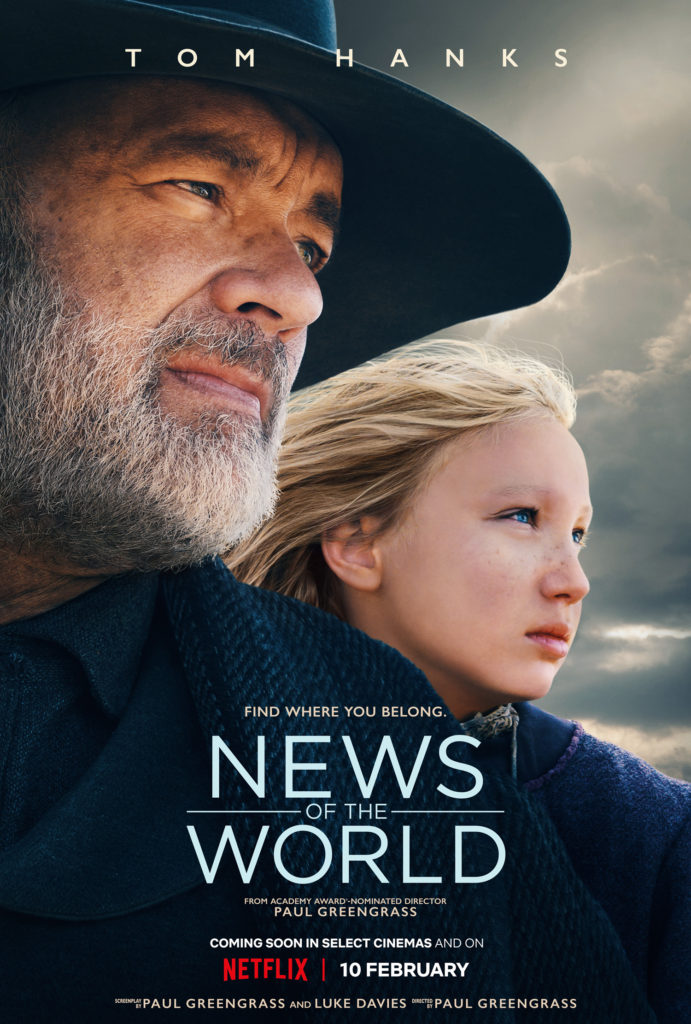

28. News of the World (United States of America)

Tom Hanks, easily, is among the most watchable actors that we have in Hollywood. In director Paul Greengrass’ leisurely western feature News of the World, the actor is in his element. The film’s vast template offers the actor to explore variations in his empathetically written part of a former infantryman Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd. Ably supported by child actor Helena Zengel, the film is a visual and aural delight with the drama in the screenplay slowly (and steadily) elevating to reach a fully satisfying finale. The cinematography and the original score ought to be among 2020’s finest.

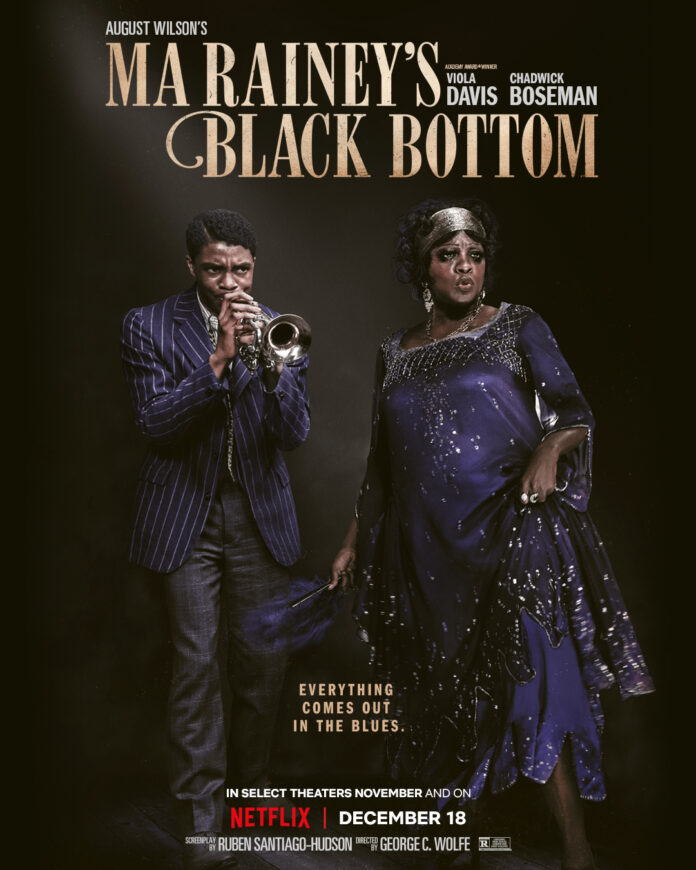

27. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (United States of America)

Based on the play by the same name, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is a compelling watch for the exact reason – it is very ‘play-like’ in its approach. While it might be a little jarring to those who wish to relish stories project on expansive canvasses, George C. Wolfe’s film delectably harps on its screenplay’s innate dramatic quotient. Set inside a recording studio, the narrative sees several ups and downs and the some remarkable writing (Ruben Santiago-Hudson) in place assures to keep us on tenterhooks. The ensemble cast is outstanding with my favourite being the late Chadwick Boseman who delivers an unforgettably wholesome act.

26. The World to Come (United States of America)

A sublime queer romance, the atmospherics of the 19th century-bound film The World To Come reminded me of 2019’s delicious Brazilian melodrama, The Invisible Life. However, the similarity stops there. Mona Fastvold’s film concentrates more unsaid emotions and the psychological mindscapes of its leading women Abigail (Katherine Waterston) and Tally (Vanessa Kirby). The intimate moments are tender and the central plot twist might shatter you a little. Even though the photography and music fittingly blend in the era and the actors emote to perfection, The World To Come might feel tad overlong to those who do not fancy languid, lyrical storytelling, I, for sure, ain’t one of them.

25. Agnes Joy (Iceland)

Iceland’s submission to the 2021 Academy Awards released in 2019 in its home country. A minimalist tale of an anxious mother Rannveig and her rebellious daughter Agnes, the film is particularly notable for its subtle local essence. The family drama template gives the film enough scope to improvise on its dramatic quotient that it does to near perfection. A series of pointed dialogues become the most noticeable element in the story that is smashingly universal despite an ambiance that is not.

24. The Girl Who Left Home (United States of America, Philippines)

The Girl Who Left Home is all about Christine (a flawless Haven Everly) who runs away from her restaurateur family to pursue her dream to become an actor and stage performer in Los Angeles. Right when she was about to touch a mega high in her career, Christine’s father passes away. She reaches out to her bereaving mother (Emy Coligado) with whom she has to mend fences for leaving home. Aside from that, Christine also deals with an unexpected eviction notice at their family restaurant whilst her agent in LA awaits her return. For Christine, it isn’t quite easy to choose between family and her passion.

Mallorie Ortega’s screenplay uses a restaurant as its primary backdrop and it gives her the liberty to show us occasional food montages. Luckily, The Girl Who Left Home does not overdo it. It merely lets the eatery provide the ambiance. Consequently, with music, food, eccentricities, and oodles of melodrama, Ortega’s film turns out to be an endearing potpourri of emotions. We notice its happy ending approaching from a distance, much like a comforting wide embrace. Needless to add, it is a sweet feeling to await Christine and her kin pine and eventually live their own sweet little fairy tale.

23. Breaking Fast (United States of America)

Not very often do we come across films that are specific about their causes and cultures. This particularity (which has numerous layers to it) makes director Mike Mosallam’s Breaking Fast a unique film to come by. The subject of the story Mo (a super-efficient Haaz Sleiman). He is Muslim and is gay. He is observing the holy fast of Ramadan. A believer, his views on Islam are somewhat rigid. He also carries unhealed wounds from his former relationship. Then he meets an affable Caucasian man named Kal (Michael Cassidy, an absolute snack).

Even though one of its leads happens to be a white man, it never develops a rescuer complex. Though the contexts differ, Karl is as needy as Mo. Breaking Fast packs in plenty of moments between the two but none of them are sexual in nature – which is refreshing. It only helps that Cassidy and Sleiman share a chemistry that is mesmerizing. I will also save an extra cookie for Cassidy’s unimaginably winsome smile.

22. Dara of Jasenovac (Serbia)

Director Predrag Antonijevic’s Dara of Jasenovac is a holocaust film in former Yugoslavia during WWII. Needless to say, it is incessantly hard to watch. With a little girl called Dara becoming the anchor of the story, Antonijevic’s becomes all the more grueling. For sure, the filmmaking bears crystal-clear knowledge on what the maker wants to communicate. There are even parts that are so designed to make us condole, the film deeply affects you. The highlight here is the work done by non-professional actors who seem to live the experience. Even though the film lacks elements of implied violence seen in The Garden of the Finzi-Continis or the dramatic potency of The Pianist, Dara of Jasenovac feels utterly personal. It is impossible to not sob upon seeing a little girl (a fabulous Bilijana Cekic) protect her infant brother. Maybe I am a sucker of such storylines but, in all honesty, I did wish that the film were to be a lot subtler.

21. Monsoon (Vietnam)

Two striking films from Vietnam in 2019-20 period were centred on queer protagonists returning from the USA to their home country. If Goodbye Mother worked more like a genuine romance with a tinge of family melodrama, Hong Khaou’s Monsoon is an understated story of a young man named Kit (Henry Golding) slowly finding his groove. Set in Saigaon, the film magical merges its lyrical quality with a certain life-like realism. The sound design is stellar in Khaou’s film filled incredible sublime moments and is headlined by a charming lead act by Golding.

20. Cowboys (United States of America)

There is something alarmingly earnest about Anna Kerrigan’s debut feature outing Cowboys. How would one, a conservative parent, react when his/her child turns out to be gender-nonconforming. We are talking about a child, not a teenager facing the so-called hormonal fluctuations. The mom is in denial and the dad attempts to concede to the situation. Then, one fine day, the little Joe goes missing.

Beautifully canvassed in Montana’s minimalist atmosphere, Cowboys emerges as a modern family fare. Without being preachy, it urges conservative parents to listen to their children. The film also duly acknowledges the legitimacy of mental health issues. While I wish this element was established a lot better on paper, Kerrigan’s debut is exceedingly intelligent as it seamlessly blends genres. It does not needlessly villainize its people but it rather examines their natural selves – flawed, hurt, and real. Lastly, Cowboys is one more step closer to making queer subjects a comfortable topic at family dinner tables.

19. A Bedsore (South Korea)

Life is not a bed of roses for Kang Chang-sik (Kim Jonggu), a retired elderly man living with his bedridden wife Gil-soon (Kang Aesim). A stay-at-home nurse named Sook-ok (Jeon Gukhyang) is the one giving them company while two of his children live in other corners of the city and one in the United States. Trouble brews in this rather peaceful setup when Kim Jonggu observes Sook-ok’s movements on a Sunday, her day off at work. Part curious and part jealous, the old man becomes a persistent stalker. One thing leads to another; an angry Chang-sik slaps the woman and demands that she leaves.

Aside from strong performances and a screenplay that is essentially the main appeal of A Bedsore, the original score (Sumgmo Kwon) is equally worth a mention. The DOP (Seung-yoon Hwang) uses the claustrophobic interior spaces of the family residence to heighten the drama to the optimum. The collective impact of every element is such that it amuses us no end that mere bedsore instigated it all.

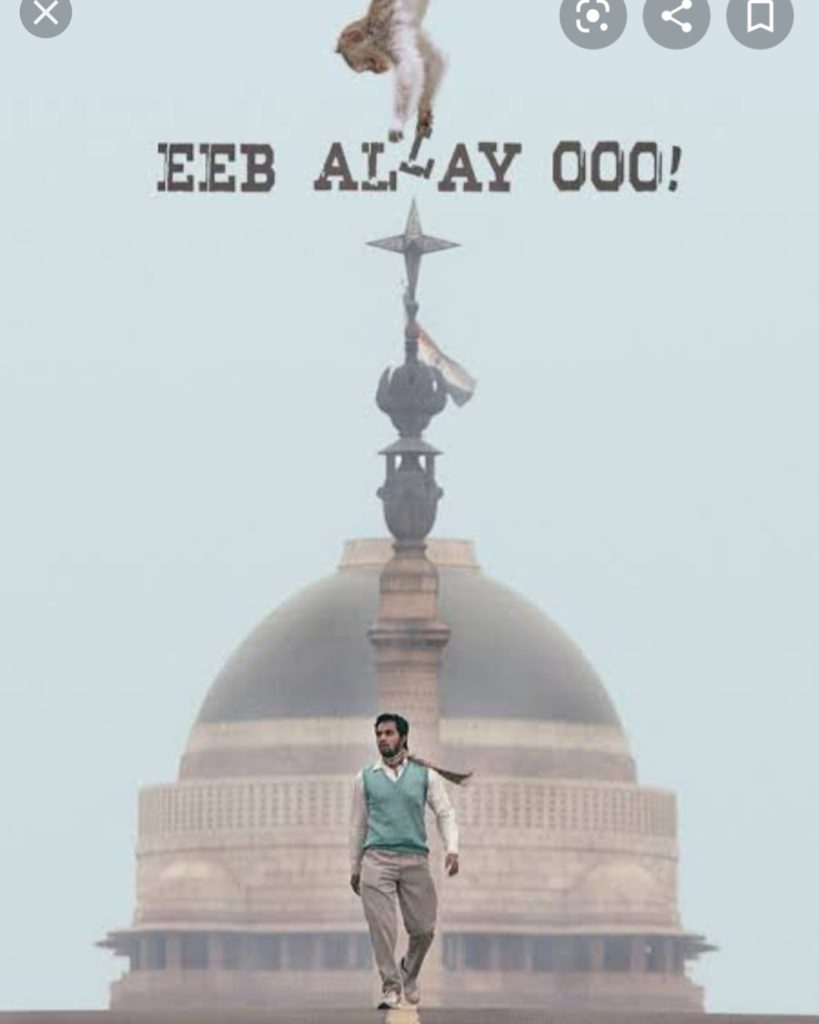

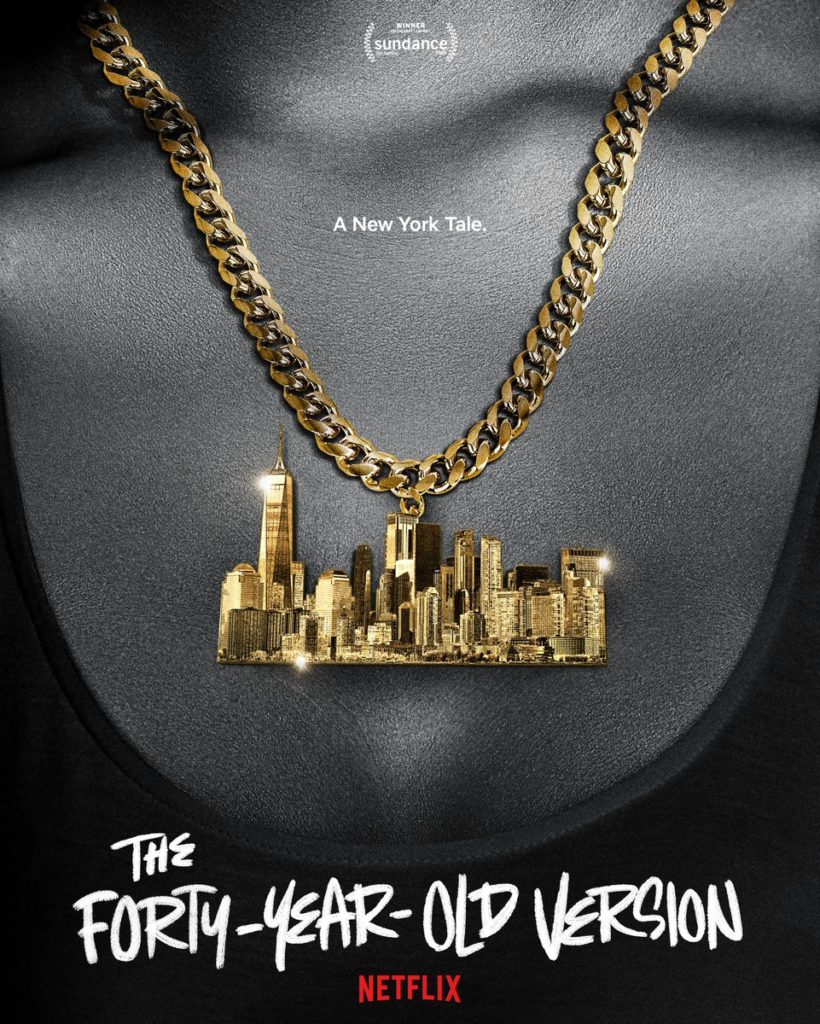

18. Eeb Allay Ooo! (India) and The 40-Year-Old Version (United States of America)

Connoisseurs of quality Indian cinema would vouch that Prateek Vats is a bona fide find. In his debut feature, the writer-director invites us to the world of Anjali (Shardul Bhardwaj), a migrant worker who ends up as a professional monkey repeller in Lutyens’ Delhi, a posh area in India’s capital city. One that makes a sharp social commentary through the eyes of a disregarded man trapped in a job that he hates, the film exposes the power hierarchies, the indifference from the government, and the endless loop that the poor of the nation is embroiled in. Powered by Bhardwaj’s able performance, the film seldom verbalizes its intentions. It merely places the camera on his activities and interpersonal relationships. The result is a riveting film that conveys a lot, nearly hitting you in the gut with its sheer courage.

Sharing the rank with Eeb Allay Ooo is debutante filmmaker Radha Blank’s semi-autobiographical comedy The 40-Year-Old Version. One that wittily welcomes us into a 40-year-old black woman’s life, the film sees Radha (Blank, also the protagonist) as a lively playwright and educator. The film’s mainstay is its uninhibited humour and energy which Blank ably peppers with a series of crackling moments and uncomplicated storytelling style.

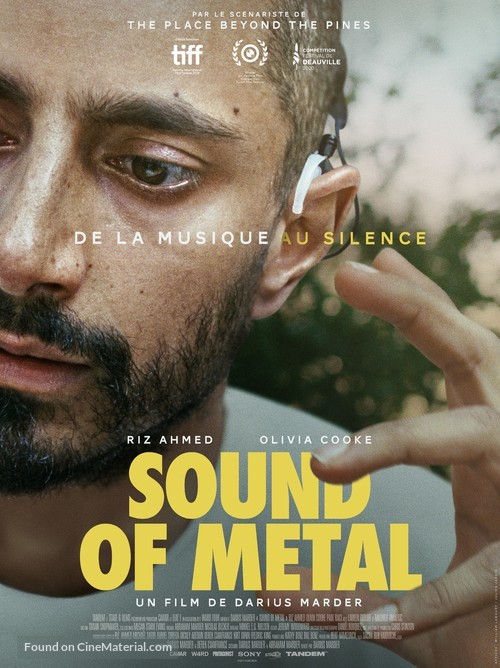

17. Sound of Metal (United States of America)

‘The tragic tale of a musician who goes deaf’ – a bad description of Sound of Metal would be just that. Darius Marder, however, is far more haunting. The protagonist Ruben’s (Riz Ahmed) plight is one that is identifiable from the word go and this is not because of deafness being a key element of the story. If Ahmed’s poignant eyes do a good amount of talking, the love story that Marder spins between him and Olivia Cooke (who plays Lou) is one that will have our hearts pining. The film has a consistently devastating tenor but that seldom lets it drown in a pit of sadness. Of course, there is a hint of melancholy that subtly engulfs Ruben’s journey. Yet the film manages to compose beauty, hope, and empathy in every frame making it one of 2020’s most riveting pieces of cinema.

16. Shirley (United States of America)

Loosely based on a chapter in celebrated writer Shirley Jackson’s life, Josephine Decker’s Shirley is an adaption of a novel by the same name (authored by Susan Scarf Merrell). One that reminded me of Wash Westmoreland’s Keira Knitley-starrer Colette, the film is a dramatic inspection of a volatile writer’s complex mind. Decker’s film closely examines the world around Shirley as she was penning a book based on the famously mysterious disappearance of Paula Jean Welden in Bennington, Vermont. Becoming a strong pivot in the tale is Rose (Odessa Young), Shirley’s friend-turned-muse-equivalent. Written by Sarah Gubbins, the film evolves into a beautifully feminist tale where women possess complete autonomy in their lives. The chapters connecting Shirley and Rose’s story to Paula’s disappearance are stunningly spooky and the performances by the duo, needless to add, are among the year’s finest.

15. Miss Juneteenth (United States of America)

The story of a parent attempting to relive the perfect life through his/her child is not uncommon in cinema or literature. Miss Juneteenth, directed by Channing Godfrey Peoples, follows a similar trail where Turquoise (Nicole Beharie) wants her daughter Kai (Alexis Chikaeze) to take part in pageant by same name. An erstwhile winner of the pageant herself, Turquoise could not make use of the benefits of her win due to Kai’s birth that forces her to quit campus. Kai, on the other hand, is least interested in her mother’s ambition for her. The third leg in the story is Ronnie (Kendrick Sampson ), Turquoise’s former partner whom she is fond of to date. The survivalist nature of the film notwithstanding, the primary appeal of the story (written by Peoples herself) is its non-judgmental approach to dealing with protagonists with disparate goals. The focus seldom wanes from Turquoise but the film confidently lets the peripheral players steal their own moments too. It is particularly impressive to see the film integrate Maya Angeolou’s poem ‘Phenomenal Woman’ within its context.

14. La Llorona / The Weeping Woman (Guatemala)

The Guatemalan entry for the Best International Feature Film at the 93rd Academy Awards is La Llorona / The Weeping Woman. The idea for the film originates from the Latin American folklore around a woman named La Llorona whose ghost wanders alongside waterfront areas in search of her children. Jayro Bustamante, who previously won huge acclaim with his debut fare Ixcanul, spins the eponymous tale around to create a mysterious domestic horror drama. Forming the La Llorona equivalent in the story is a devoted housekeeper Alma (María Mercedes Coroy) whose presence haunts former army general Enrique Monteverde’s (Julio Diaz) home. Bustamante’s filmmaking gleams with the artistry that we saw in his fabulous debut with the sound design, original score, and cinematography amply contribute to creating the absurdly spooky atmosphere that the film works around.

13. The Strong Ones (Chile)

Set in a remote South Chilean town, Hidalgo’s film is a rather conventionally staged love story between two unalike men. Lucas (Samuel González), an architecture student, takes a trip to visit his sister. In a chance encounter, he comes across Antonio (Antonio Altamirano), a sailor and part-time actor for historical reenactments of the capture of Valdivia’s fortresses. In their first meeting when Antonio drops at Lucas’s place to drop off firewood, we sense sexual tension seething out of the frames. With the tantalizing manner in which the men and their gazes are captured, we get a hint of what lies ahead. The scene closes with a telling rear-view mirror shot through which Antonio stares at Lucas.

The Call Me By Your Name déjà vu is pretty obvious and we do see the climactic moment approaching from a distance. That said, the staging and the cinematography coupled with the leads’ smouldering chemistry make sure that we care for their well-being – making Hidalgo’s film a genuine charmer.

12. Cicada (United States of America)

It is astonishing when cinema dares to emotionally bare its protagonists. In directors Matthew Fifer and Kieran Mulcare independent fare Cicada, we are invited to the broken world of Ben (Fifer). The young queer Caucasian man with dreamboat looks by his side might look as regular as any person with a boring desk job. What he conceals within are truths and wounds – unspoken and unhealed.

Personally, Cicada left me with a heavy lump in my throat. It is a cinematic experience I would cherish for a while simply for the fact it felt personal and immersive. The storytelling is sensitive and the characters are straight out of life. It only helps that the film does not wear its sexuality on its sleeve (like many queer-themed films do) as it has more profound worries to address.

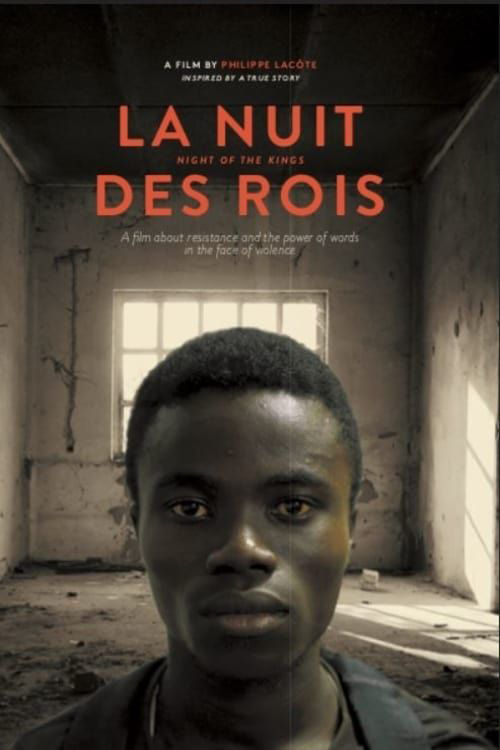

11. Night of the Kings (Ivory Coast)

A film from Ivory Coast, Night of the Kings is a prison film set in one of Africa’s most notorious prisons – the MACA correctional facility. The freshness in the plot is not primary due to its setting but for its Arabian Nights-like ambience. A new inmate is demanded to tell a story that lasts till the sunrises in his first night in the prison. In the bargain, he is will be spared from being murdered. With a premise as eerie as this, it is to nobody’s wonder that Philippe Lacote’s film bears more traces of a bona fide horror fare than a gritty jail drama. The cinematography lends arresting shades of terror and so do the dialogues in the chapter where the leading man narrates the story of Zama King.

10. The Assistant (United States of America)

Directed by Australian filmmaker Kitty Green, the film kicks off in the most mundane way possible. We are introduced to the routine desk operations of a junior assistant Jane (an astounding Julia Garner) in a film production company’s office. There are limited dialogues and interactions that happen within her place of work. Soon enough, The Assistant transforms into a severely intimidating and eventually shocking story. One that is hugely relevant in the age of the ‘Me Too Movement’, the film uncovers the dual faces of corporates besides profoundly addressing phenomena such as power hierarchies and male supremacy. The final shot of Jane staring at the window of her boss’s cabin from the pathway outside might be subtly staged but is among the most riveting scenes from any film in 2020.

9. Promising Young Woman (United States of America)

Promising Young Woman kicks off in an amusingly campy fashion. The setting is that of an uptown bar. An attractive young woman is in an inebriated state with a batch of leery men itching to take her home. Surprisingly, the woman is not what she appears to be. She does go home with a dude named Jerry leading to an episode that he would remember for a lifetime. The woman is Cassandra alias Cassie (Carey Mulligan). She is neither a hooker nor a nymphomaniac. She goes barhopping every weekend for a reason.

Not a genre film in any way, Emerald Fennel constructs a savagely feminist story in her directorial debut. While it needs to be seen how the public would take to its unusual climactic jolt, the screenplay astutely connects the dots as Promising Young Woman closes – making the unexpected twist worthwhile. Powered by a stupendous central performance and a fine understanding of womanhood, the film throws light on good female friendships. Fennel asserts how every woman ought to shoulder each other by not giving into the rules pronounced by the male-deifying society. At some point, Promising Young Woman stops being a chronicle of abuse as it effectively questions our social conscience besides provoking us to re-evaluate our morals. A riveting fare in every sense of the word, one only wishes how Fennel’s film was a little more consistent – tonally, visually, and emotionally.

8. I am Thinking of Ending Things (United States of America)

The most striking side of Charlie Kaufman‘s psychological thriller I am Thinking Of Ending Things is provided by its telling dialogues. It blends humour in its conversations that are often filled with grief and pathos. The film is also remarkably feminist in various ways. It boldly questions how society assigns the onus of a man’s bad behaviour to a woman – be it a mother, a wife, or a partner. Another side of the story that appeals are the way it reads a woman’s thoughts even though she never really actions them. Here is another of its brilliant quotes,

“People stay in unhealthy relationships because it’s easier. Basic physics. An object in motion tends to stay in motion. People tend to stay in relationships past their expiration date. It’s Newton’s first law of emotion. People stay in unhealthy relationships because it’s easier. Basic physics. An object in motion tends to stay in motion. People tend to stay in relationships past their expiration date. It’s Newton’s first law of emotion.”

7. No Hard Feelings / Futur Drei (Germany)

Set in Germany, Faraz Shariat’s No Hard Feelings was the closing film at the New Fest New York LGBTQ Film Festival. A crackling fusion of woes connected to race and sexuality, the film is embellished with a story that transcends cultures and belief systems. The gay romance gives scope to a series of beautiful love scenes whereas the actors (Benjamin Radjaipour, Eidin Jalali, and Banafshe Hourmazdi) walk away with our hearts. Shariat’s film is soft and simple in its storytelling format whereas its people and emotions are deliciously complex.

6. The Disciple (India)

Chaitanya Tamhane’s debut film Court was one that stunned cinema lovers to the core – I would say, primarily for its sheer audacity among its long list of merits. Naturally, the filmmaker’s second feature would evoke a higher sense of anticipation. The Disciple is one that felt immensely personal due to my interest in Indian classical music forms. The film talks about a youngster named Sharad (Aditya Modak) who trains with his teacher (Dr. Arun David) in Khayal (a Hindustani classical music variant) before he took a plunge into a prized competition. The contours soon shift when it focuses on an older Sharad and his turmoil vis-a-vis the excellence he is striving to touch base. Through sharp stares, marvelous expressions, and an astounding physical transformation, Modak becomes the life of The Disciple’s textured screenplay which great scope for the viewers to interpret nuances from. The original score and reflective plot-twists make sure that Tamhane’s film leaves you an unusual yet thoroughly enriching experience.

5. Another Round (Denmark)

Another Round is about four male schoolteachers Martin (Mads Mikkelsen), Tommy (Thomas Bo Larsen), Peter (Lars Ranthe), and Nikolaj (Magnus Millang). Dabbling with typical middle-age woes of familial, professional, and social nature, the foursome makes an eventful decision at Nikolaj’s 40th birthday party. They announce to take up a pseudoscientific experiment as proposed by Norwegian psychiatrist Finn Skarderud. The deal is to consume alcohol in such a way that it remains precisely 0.05% of one’s blood-alcohol content. This exercise, as interpreted by the men, was bound to transform their lives. Inspired by Ernest Hemingway, the four friends agree upon an 8 pm curfew besides a rule to shun alcohol over the weekend.

The most delightful chapter in this tragicomedy is the closing sequence. Vinterberg intersperses conflicting emotions (grief, relief, and celebration) without making them appear flippant. As Martin dances gleefully with his freshly graduated students, we look at him with awe and thrill. We do not erase the grief he has curbed within but there is also the happiness of his family life taking off yet again. It is a compound mishmash of feelings and Vinterberg skillfully expresses it all through Martin’s happy-dance.

4. Dear Comrades (Russia)

It is its monochrome frames and the backdrop of a historic massacre that initially drove me to Andrei Konchalovsky’s Dear Comrades! Within moments, the film turns out to be a fine chronicle of the central character Lyuda’s (Julia Vysotskaya) immediate domestic and workspace. One who works for the Communist Party, Lyuda’s influence does have a role in easing out the economic imbalance plagued by the nation in that period. Notably enough, the scenes that set the tone for her character are high voltage which is bound to ease you into her mindscape. The story soon races into its key twist – the shooting of a demonstration of workers in Novocherkassk – evoking motherly angst within Lyuda. The series of events ends up transforming her worldview while also making her question her belief in Communism. While the all black-and-white setup is fascinating (much like Pawel Pawlikowski’s 2018 music romance Cold War), it is the vulnerability expressed by Vysotskaya as a hapless mother in search of her daughter is what takes the cake for Dear Comrades!

3. Never Rarely Sometimes Always (United States of America)

To spill the truth, nothing quite happens in Never Rarely Sometimes Always directed by Eliza Hittman. It unhurriedly follows a sequence of events when 17-year-old Autumn Callahan (Sidney Flanigan) discovers that she is pregnant. Along with her cousin Skylar (Talia Ryder), Autumn embarks on a journey to New York City. Their mission is to abort Autumn’s baby – something that isn’t legal in Pennsylvania without parental consent. There are no gargantuan twists in Hittman’s story, which, surprisingly, is the most attractive aspect of the screenplay (by Hittman). Never Rarely Sometimes Always pays minute attention to detail. Every expression, every spoken dialogue and every glance come for a reason. They might not be of the surprising kinds but the way Hittman lands them all in a vulnerable, bold and thought-provoking story is worth a standing ovation. More than anything else, Hittman’s film forces you to think about teenage pregnancy and its aftermaths. It does not let you judge its characters for a moment but leaves a strong aftertaste. Flanigan’s utterly understated performance is easily among the year’s best.

2. Nomadland (United States of America)

What impressed me the most about Nomadland is how the film and its lead are both uncompromising. The very aspect passively reminded me of 2018’s crackling Leave No Trace. The tone is decidedly unenergetic and the film wouldn’t appeal to those who are in for a topsy-turvy plot. Zhao’s film unfolds like a lazy Saturday morning to which McDormand and the crew add oodles of flavour – much like a comforting cup of coffee. Calm yet a vivid portrait of an under-represented community within the US society, it wouldn’t be wrong to rank Nomadland among the finest films of 2020, if not call it the very best.

1. Minari (United States of America)

After several afterthoughts, I settle for Minari as 2020’s finest feature film. Set in the quaint countryside of Arkansas, Mirani follows the life of a Korean-family who arrives from California. Working in a local hatchery, Jacob (Steven Yeun) and Monica (Han Ye-ri) have different ambitions despite their love for each other. If Jacob wishes to build a farm of organic Korean veggies around their unappealing, rustic home, Monica prefers the urban setup of California for reasons more than one. Things take an interesting turn when Monica’s mother Soon-ja (Youn Yuh-jung of Bacchus Lady) travel from Korea to take care of the children, David and Anne. Foul-mouthed and full-of-life, the old lady gets a bittersweet welcome from the children, especially David. As Minari evolves through a series of events, their equations change – some for good, some for worse.

Director Lee Isaac Chung puts together a fascinating tale where several sides of a non-Caucasian family living in the USA stand addressed. Minari is also an effective marital and family drama with the emotional portions holding immense potency to move you to tears. The finale, which involves a tumultuous event and calming final shot, is an example of how extraordinary writing, masterful execution, and world-class acting would co-exist in a framework that is designed to perfection.